Noplace is a net art work created by MW2MW (Marek Walczak and Martin Wattenberg) that explores ideas of utopia, fantasy and desire. The artwork site invited users to contribute words relating to ÔÇÿa current desire or goalÔÇÖ and used these terms to generate animated visual narratives using photographs found on the internet. The resulting films are algorithmically generated ÔÇÿpersonalised visions of utopiaÔÇÖ, each one unique but built from the same ÔÇÿaggregated cultural memoryÔÇÖ of the internet in the 2010s (figs 1 and 2).1 It was commissioned by Tate for its Intermedia Art pages, and was online for one year from August 2008. The page on the ░ı▓╣│┘▒ÔÇÖs website provided a brief introduction to the work, two commissioned essays, a video interview with Walczak and a link to launch the artwork.2

Fig.1

Still from Noplace 2008 by MW2MW

┬® Marek Walczek and Martin Wattenberg

Fig.2

Still from Noplace 2008 by MW2MW

┬® Marek Walczek and Martin Wattenberg

The launch page of Noplace contained introductory text about the artwork, inviting users to create their own vision of a ÔÇÿparadise, heaven or pessimistic utopiaÔÇÖ by submitting ÔÇÿa few words about that place that has not yet come into beingÔÇÖ.3 Clicking the link to ÔÇÿcreate your own noplaceÔÇÖ launched a Java applet that generated and displayed an animation. As the visitor typed words or sentences into a text field, associated images came together to generate a unique animation. This was made possible by an underlying database of images from the image-sharing site Flickr, which the artists had ÔÇÿscrapedÔÇÖ.4 These images had been tagged by those who created and uploaded the images, and to these Wattenberg and Walczak added tags associated with ÔÇÿutopian vocabularyÔÇÖ such as ÔÇÿrapture, nirvana, communismÔÇÖ.5 A userÔÇÖs unique animation could be viewed on the siteÔÇÖs archive for ÔÇÿothers to contrast with their ownÔÇÖ.6 The animations can no longer be viewed but their titles can be seen via the Wayback Machine. The titles are taken from the user prompts, for example:

noplace is myself and my lover, united in God\ÔÇÖs immanent presence

noplace is cheese face and noise and skateboard pen

noplace is a sea of underwater sleep that endlessly flourishes diving and diving like a coral reef.7

At the end of each movie was a scrolling list of credits referencing the sources of the images used in the movie, as required by Creative Commons (CC) copyright licencing.

Making and commissioning

Fig.3

Installation view of Noplace in Synthetic Times at the National Art Museum of China, Beijing, 2008

The version of Noplace commissioned by Tate forms part of ÔÇÿa series of physical and online art installations exploring visions of paradiseÔÇÖ created by Wattenberg and Walzcak between 2007 and 2008.8 The artworks in the series each ÔÇÿtake feeds from networked society ÔÇô images, sound and text ÔÇô as raw material to generate shared and personal utopiasÔÇÖ.9 The first version was a six-screen installation. It was included in the exhibition Video Vortex at the Netherlands Media Art Institute, Amsterdam, in 2007, curated by Annet Dekker.10 The following year another six-screen installation was included in the exhibition Synthetic Times at the National Art Museum of China, Beijing, curated by Zhang Ga (fig.3).11 In both these installations visitors could interact with the work using a touchscreen interface. In addition, as described on the Noplace website, ÔÇÿthe tag sequencer not only finds narrative threads within each cluster, but also finds parallel narratives within different projections, so synchronizing divergent utopias and allowing for a reading across human wishes and desiresÔÇÖ.12

As a result of experiencing Noplace in Beijing, Kelli Alred (then Dipple), Curator of Intermedia Art at Tate Media from 2007┬¡ to 2011, invited Wattenberg and Walczak to create a new version for ░ı▓╣│┘▒ÔÇÖs website. Comparing the digital and physical versions of the work, Wattenberg recalls how he and Walczak loved the large scale of the projections in the installation, but their desire to present the work to a wider audience led to the web version.13

The starting point for the commission was collage, in both a metaphorical and technological sense. Walczak and Wattenberg were interested in collage as an expanded process through which disparate things are brought together. As Wattenberg has described, this understanding of collage relates to the way things frequently ÔÇÿbump into anythingÔÇÖ on the web.14 At the time of the commission this was particularly evident in sites such as Tumblr, Flickr and YouTube, where large quantities of audio-visual content were starting to be uploaded by the general public. Yet despite this collision of ideas and stories made possible through Web 2.0, Wattenberg has reflected that from a technical standpoint, it was ÔÇÿhard to place images in direct juxtapositionÔÇÖ.15 And so, as well as by the possibilities of collage, the artists were driven by the technical possibilities of combining images dynamically on the web, in finding ways to place images on top of one another through techniques of transparency and overlay.

Reception and interpretation

Noplace was created during a period that saw the rapid increase in online user-generated content. The work responded to growing archives of content by ÔÇÿcuratingÔÇÖ the images of others and ÔÇÿdrawing on the creativity of the internet as a wholeÔÇÖ.16 This was achieved through a collective reflection on the idea of utopia also referred to as ÔÇÿnoplaceÔÇÖ. As Wattenberg points out, ÔÇÿnoplaceÔÇÖ also references the virtual, ÔÇÿthat the importance of geography has really become diminishedÔÇÖ.17 For Walzcak and Wattenberg, 2008 seemed to be a utopic moment for the internet. Created in the context of global conflict, in particular the Iraq War, the work explored the potential for the internet to act as a space for imagination and communication. This is reflected in the text of the ÔÇÿWhatÔÇÖ section of the artworkÔÇÖs website: ÔÇÿThese paradise types are endgames of ideological constructs, whether a vision of a classless society or a scientistÔÇÖs vision of a sustainable environmentÔÇÖ.18

Tate commissioned two essays to help contextualise Noplace for its audiences. These were published on the Intermedia Art pages alongside a link into the work. In ÔÇÿWelcome to the Desert of the DigitalÔÇÖ media theorist Charlie Gere draws a parallel between Thomas MoreÔÇÖs Utopia (1516), the ÔÇÿnoplaceÔÇÖ of the North American desert, the ÔÇÿseries of desert wars being waged in the Middle EastÔÇÖ and the ÔÇÿnoplaceÔÇÖ of the digital:

ÔÇÿDigital media, artefacts inscribed with material representations of digital data, may exist but the digital itself does not exist. ÔÇ£There is no there thereÔÇØ. It is just zeroes and ones. In whatever form or medium it may be materialised it is itself nothing but difference.ÔÇÖ19

Like Wattenberg and Walczak, Gere contemplates the web as a space to ÔÇÿgain insightÔÇÖ into our social, political and ecological condition.20

There was a shift in the curatorial approach to ░ı▓╣│┘▒ÔÇÖs net art commissions in 2008. Rather than being commissioned as a single net art work to be hosted on ░ı▓╣│┘▒ÔÇÖs website alongside an accompanying essay ┬¡ÔÇô as had been the approach since 2000 ÔÇô Noplace formed part of a wider programme and came under the theme of ÔÇÿVideo as a Social AgentÔÇÖ. As well as Noplace, this included Underscan, a public art commission by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, the broadcast of Lynn Hershman LeesonÔÇÖs Curing the Vampire and an interview with the artist Mark Amerika.21 In an essay commissioned for the Tate website, archaeologist Michael Shanks reflects on the theme of ÔÇÿVideo as Social AgentÔÇÖ by reflecting on how all these works in some way celebrate the potential of the Creative Commons. They each also consider the performative space of media, taking it to be ÔÇÿmodes of engagement between people, ideas, artifacts and settings as they are about the communication of messages or the representation of ÔÇ£realityÔÇØÔÇÖ.22

In her article ÔÇÿMemory Work in the Digital AgeÔÇÖ, Hillary Savoie included Noplace to illustrate the changing representation of collective memory in new media ÔÇÿas individuals increasingly write their own stories into ÔÇ£memorialsÔÇØ on interactive mediaÔÇÖ.23 Through this and other examples of digital projects, Savoie explored the way that individual memories become common, universal stories. In Noplace, for instance, the universal or common experience can be found in the questions posed by its creators ÔÇô ÔÇÿwhat is paradise or utopia?ÔÇÖ ÔÇô as well as in the images scraped from Flickr and used to create the videos on the site.

The artistsÔÇÖ practice

Noplace was created by MW2MW, the collaborative practice of Marek Walczak and Martin Wattenberg. MW2MW was established in 1997 after the artists met through the mailing list World Wide Web ArtistsÔÇÖ Consortium (WWWAC). Both artists work independently in addition to their long-term projects as part of MW2MW.

In his work, Marek Walczak explores how people participate in physical and virtual spaces. In 2008 he collaborated with the radio artist, composer, performer and writer Helen Thornington on Adrift, an internet performance event that took place between Linz, Austria and New York.24 This experience led Walczak to collaborate with Martin Wattenberg on a series of projects. Walczak is now part of the collaborative CIVIC.SPACE, creating interactive civic art design and public art with Wes Heiss.25

Martin WattenbergÔÇÖs work intersects mathematics, computer science, art and journalism. His interest in machine learning, data visualisation and collective intelligence is demonstrated in Map of the Market 1998 for the website Smartmoney.26 One of the first visualisations on the web displaying live stock market data using a ÔÇÿtreemapÔÇÖ technique, it allowed users to track hundreds of stocks at the same time.27 In 2003, Wattenberg created History Flow with Fernanda Viegas, a visualisation of the edit history of Wikipedia.28

Fig.4

Screenshot of Wonderwalker 2000 by MW2MW

Image courtesy the artists

Fig.5

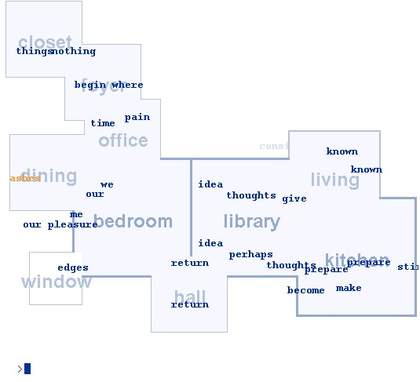

Detail of Apartment 2001 by MW2MW, 2D view of user-generated apartment

Image courtesy the artists

Walczak and Wattenberg have come together as MW2MW on several long-term projects, including Wonderwalker 2000, a commission for Gallery 9, an online exhibition space for web-based works hosted by the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (fig.4). The website reimagines the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century wunderkammer as a ÔÇÿphantasmagoria of web objects, whose reason for placement in the collection is dependent on an independent eyeÔÇÖ.29 Their web-based work Apartment 2001 is a precursor to the experiments of ÔÇÿspatialising memoryÔÇÖ developed by MW2MW in Noplace.30 It was inspired by the idea of the ÔÇÿmemory palaceÔÇÖ or ÔÇÿmethod of lociÔÇÖ, a mnemonic technique that utilises visualisation to map memories onto imagined spatial environments. As visitors to the website typed words into a tab, a floorplan of an apartment appeared on the screen (fig.5). To create this, words had been organised into themes and ideas, each of which were associated to particular rooms. Noplace was a continuation of the idea expressed in Apartment that ÔÇÿwords can create spaceÔÇÖ;31 it was about inviting people to imagine and spatialise individual and collective utopia.

Others involved in Noplace include software engineer Jonathan Feinberg, Rory Soloman and Johanna Kindvall. Feinberg developed the software for Noplace after having collaborated with MW2MW on both Wonderwalker and Apartment. He has also contributed to net art works by other artists, including Golan LevinÔÇÖs interactive data visualisation of teenage heartbreak, The Dumpster 2006, which was commissioned by Tate as part of the same programme.32 Rory Solomon, a computer programmer and artist, put the installation together with Walczak in China. Johanna Kindvall, WalczakÔÇÖs partner and frequent collaborator, contributed illustrations and general guidance.33

Technical narrative

The work was created in two steps. The artists first collected images and tags in a database, and then they designed a process for selecting and combining those images in collages, according to words or sentences input by the users. Although contemporary descriptions of the work state otherwise, Noplace did not have a sound element, due to the limited availability of usable online sources.34

Before every exhibition, or version, of Noplace, the artists compiled images and tags using Flickr and its RSS (Really Simple Syndication) feed feature. RSS feeds were created by Flickr to allow users to receive notifications when they had new comments on their images, or when new photographs were uploaded to public streams.35 These feeds made it possible to automate ▓Ð░┬2▓Ð░┬ÔÇÖs selection of images based on specific tags, and on the type of licensing the images held. These images and their tags were stored in a database, and the tags were then analysed and grouped into eight ÔÇÿroomsÔÇÖ or ÔÇÿnoplacesÔÇÖ: AllahÔÇÖs Garden, American Dream, Communism, Ecological Earth, Nirvana, Positivism, Rapture and Urban Utopia.36 Walczak describes the use of tags as follows:

We chose a dozen keywords for each world or universe or ÔÇÿnoplaceÔÇÖ. Each ÔÇÿnoplaceÔÇÖ had one set of twelve keywords and then there were random words added because every Flickr image had its own set of tags and we included that within the search parameters, so that whoever typed, like, ÔÇÿribbonÔÇÖ, they would actually see a capitalist ribbon, for example.37

Words or sentences input by users would also be analysed. An in-built thesaurus identified related words so that equivalents were found for words that were not included in either the keywords or the Flickr user-tags.

Fig.6

Still from Noplace 2008 by MW2MW

┬® Marek Walczek and Martin Wattenberg

To create the video collages, the artists made use of a Java applet, a rich web application that uses Java and the Java Virtual Machine in the userÔÇÖs computer to display complex software via the browser.38 The applet would combine the images from the database based on a pre-existing timeline. Mark Wattenberg describes how the applet would structure the images: ÔÇÿIt would say ÔÇ£At three seconds in, switch to nirvana, here are the pictures you want to show and hereÔÇÖs the type of animation you would doÔÇØ. Then it would say, ÔÇ£Okay, now, at seven seconds in, do thisÔÇØ. So, it was almost like creating a little play, rather than a movieÔÇÖ.39 For each ÔÇÿnoplaceÔÇÖ, different layering effects were used to create unique animations, a device already used in Apartment. The animations were often based on colour, so that different colours had different transparencies, for example (fig.6).40

It is important to highlight how difficult it was to superimpose images in a code-based, generative way. Photoshop, already a popular desktop application, supported image transparencies and superposition, but it was not possible to replicate this on the web. The first step in creating the ÔÇÿnoplaceÔÇÖ applet was therefore to programme the ability to make this type of juxtaposition. The authors describe the creation and layering of the animations as an iterative process of testing that carried over multiple projects. The final step was to add the words input by the visitor, along with the list of credits, to the end of the animation on the applet, to comply with the Creative Commons licencing rules. The animations could not be downloaded by visitors to the site, but MW2MW created and saved FLV (Flash Video) files as a form of documentation. These videos are still accessible to the artists, although no longer online.

The project teamÔÇÖs interviews with Wattenberg highlight the groundbreaking nature of Java applet technology at this point, and his own enthusiasm about its possibilities: ÔÇÿJava gave you a much more expressive way to use the medium, just technologically, than HTML did... you could do whatever you wanted back then in an appletÔÇÖ.41 Java applets allowed websites to react to a viewerÔÇÖs input in real time. They also looked very different from pages made using HTML, which Wattenberg considered ÔÇÿan artistic statement in and of itselfÔÇÖ.42 Wattenberg emphasises the importance of sharing information with the growing community of applet users. This happened mostly online, via a network of personal web pages where people would publish their experiments, with an important institutional centre at MITÔÇÖs Media Art Lab.43

The applet and front-end interface of Noplace were developed by Wattenberg and Walczak; the backend was mostly the work of Jonathan Feinberg, building on his software development for Wonderwalker.

The work was commissioned to be active for a fixed term, and so, as was the case with Nonrepetitive 2011 by Achim Wollscheid, the work was taken offline after a year.44 At that point the artists created an archive of the work, with examples of the animations and stills created in the process. This points to the importance of documentation and the potential use of that documentation to represent the work.

Current condition

Although Noplace is no longer accessible, some elements can be experienced through the archive recordings made by the Wayback Machine.45 Here we find information about the work and the instructions for those visiting, but we also encounter the limitations of web-recording. It is difficult to get a sense of how the website would have originally appeared since most aspects of its design have disappeared and the user interface has not been captured. While there would have been images and preview videos, what we now experience is a white page with Times New Roman font.

In 2020 we opened discussions with the artists about the future of the work. The artistsÔÇÖ priority was to care for the general concepts of the work around utopias and spatialisation in the current social and technological context. Held during the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic, the discussions reflected wider societal questions over how the world would, or could, change in the wake of a global health crisis. The notion of utopia thus provoked very different ideas and images to those gathered in 2008.

From a technological perspective, the current possibilities for 3D spaces on the web and the developments of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning could enable an expansion of the resulting images and animations in Noplace. However, the artists felt that the historical version would be best suited to the context of a retrospective or historical exhibition. Wattenberg is still able to run the front-end software, but no longer holds the datasets of images, possibly because they were initially stored externally, given the amount of memory they required. It was felt that re-scraping images for use in the historical version would not be appropriate, as these would be anachronistic.

Conclusion

The idea of the ÔÇÿnon-placeÔÇÖ had significant cultural currency within the net art field after the publication of sociologist Marc Aug├®ÔÇÖs book Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity (published in French in 1992; English translation published 1995). Aug├®ÔÇÖs work was widely referenced in exhibition texts, including in a show of the same title at the Frankfurter Kunstverein in 2002, and the exhibition Ctrl [Space]: Rhetorics of Surveillance from Bentham to Big Brother in 2001ÔÇô02 at ZKM, Karlsruhe.46 Artists have used the idea of the non-place to describe works imagining both virtual and digital or digitised worlds. These include Marc LeeÔÇÖs artificial and virtual reality project 10,000 Moving Cities ÔÇô Same but Different 2018, which explores the increasing globalisation and homogenisation of urban centres, and Neal WhiteÔÇÖs Office of Experiments 2004, a collective project that blends experimental geography with research into the infrastructures of mobile and media technologies.47 While these examples each focus critically on the ways in which the physical and digital are enmeshed and the resulting power dynamics, Noplace is notable for its openness to the imagined landscape as paradise or utopia rather than as pessimistic dystopia. Despite the use of positive vocabulary to underpin the ÔÇÿcompositionsÔÇÖ, however, the resulting collages were mostly fragmented, grey and shadowy in colour, and crowded or busy (compared to ideas of paradise as open, calm and clear spaces).

Writing about the work fifteen years after it was made, it is clear that societal conceptions of utopias ÔÇô as free from technology, sustainable and with more equitably shared resources ÔÇô have changed, as has the technology used to generate such visions. With the release of Dall-E and other AI image-generation software, it is now possible to enter any keywords and the software will query the metadata of gigantic databases of images (also scraped from the web) to return often surrealist or dream-like visions.48 Artist and theorist Joanna Zylinska argues that these AI constructions are ÔÇÿwarped dreamsÔÇÖ, presenting biased versions of things we have already seen rather than creating anything genuinely new.49

By authoring or recombining content using pre-set animation types and a limited range of keywords determined by the artists, Noplace perhaps bears closer resemblance to, and builds on, the raft of ÔÇÿdatabase cinemaÔÇÖ projects prevalent in the early 2000s. Thomson & CraigheadÔÇÖs Template Cinema 2004, for example, queried live internet webcams, live online radio stations and a database of scraped chat room logs to generate short films with inter-titles, soundtracks and a rule-based narrative flow (a second screen often showed the ÔÇÿcreditsÔÇÖ or sources of the material).50 Lev ManovichÔÇÖs Soft Cinema project from 2002 combined split-screen windows with footage filmed by the artist, colour swatches, pre-recorded music and voiceover scripts.51 With the increasingly widespread use of AI tools, and considering the scale and speed at which they work, we must work to ensure these important early art precedents are not obliterated in the creation of new visions of utopia.