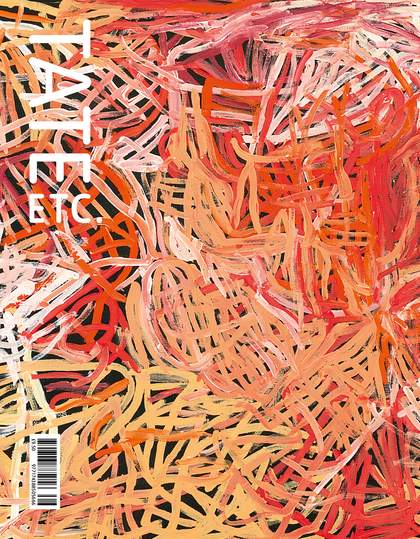

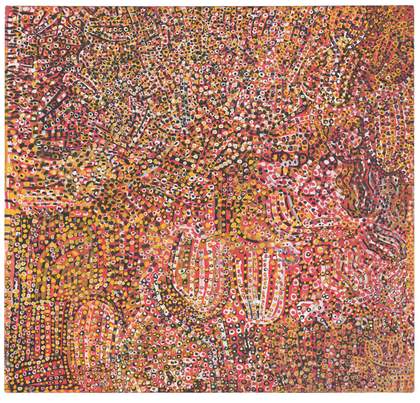

Emily Kam Kngwarray

Mern angerr 1992

Ā© Emily Kam Kngwarray / Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2025. Collection BeĢrengeĢre Primat. Courtesy of Fondation Opale, Switzerland

The inland plains of Central Australia are traversed by ephemeral rivers and creeks, as well as crenellated crests of quartzite and sandstone. Alhalker Country lies partially within a stand of these low-lying parallel ridges: a sanctuary of hidden springs, shelters and secret places. Throughout the spinifex grass sandplains, the fruits of the intekw (fan flower) attract ankerr (emus), and along the creek beds and hollows of the hinterland, the yellow, pea-like flowers of anwerlarr (pencil yam) proliferate. Below ground, the kam seedpods and anwerlarr tubers swell. Following summer rains, stands of perennial alyatywereng (woollybutt) grasses seed. Deep grooves in shelters throughout the region mark the long passage of time, and ageless symbols etched upon the rock by the ancestors tell the stories of place. The enduring presence of Ancestral Beings is tangible and celebrated in song and dance. This is the world of Emily Kam Kngwarray.

Kngwarray was born in Alhalker Country in the early 20th century and was known to her family by the name Kam. The practice of naming a person after Country, the term often used by Aboriginal peoples to describe the land and context to which they are connected, reflects a worldview that has the inseparability of people and places at its core. Kngwarray experienced the onset of the colonial frontier first-hand as a young girl and subsequently witnessed the consolidation of industry in the region when pastoralists ā and to a lesser extent, missionaries ā competed to harvest labour and souls for their enterprises. In the latter part of the 20th century, following the annex- ing of her Country for agricultural interests, access to her birthplace was limited by cattle station owners. In 1976, the Aboriginal Land Rights Act was passed, and in the same year the lease to Utopia Station, one of the largest and most populated settlements in the region (close to where Kngwarray lived), was acquired by the Aboriginal Land Fund Commission on behalf of the Traditional Owners. As Knwarray remembered:

The judge gave the country back after everyone had shown it to him. Then we painted ourselves with designs from the Country. After that we danced, āThis is the Countryā.

Kngwarrayās artistic journey began when she joined Utopia Womenās Batik Group, established by Jennifer Green in the late 1970s. She was in her mid-60s, and the oldest member of the group, living at the time in the arlweker (womenās camp), and had the energy and enthusiasm to devote to the practice of dyeing cloth. She was, as she said, āthe boss of batikā, but her attention shifted to painting on canvas in the mid-1980s.

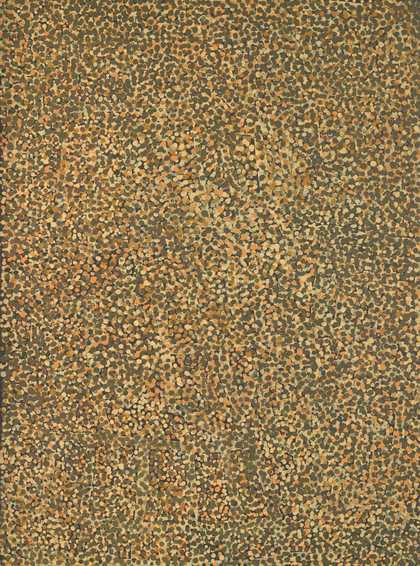

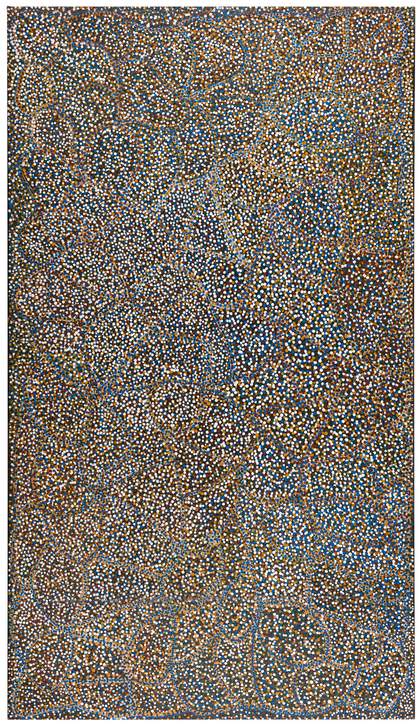

Emily Kam Kngwarray

not titled 1981

Ā© Emily Kam Kngwarray / Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2025. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1983. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Australiaās digital team

Understanding the motivations underpinning Kngwarrayās works is hampered by the scant documentation available. Sometimes the titles of her works provide clues and point to consistency across time and media. However, the advice and interpretations of Kngwarrayās descendants are invaluable, allowing due consideration for the passage of time since the works were made, and the passing of the artist. Meaning is often in the eye of the beholder.

In an untitled work on cotton, created in 1981, the distinctive features of Kngwarrayās later practice are presaged in an orchestrated complex of strokes, grids, undulating lines and roundels of varying sizes. This work is a tour de force that maps the cultural meridians of Alhalker and its neighbouring older āsiblingā Country Anangker, employing the metaphor of the anwerlarr (pencil yam) and its kam seeds and seedpods. Occasional arc motifs, possibly referring to the central node of the plant, are depicted amid the organic geometry of arla (vines) and artekerr (roots). Kam seedpods can be seen interspersed among the vines and tubers.

When an image of this work was shown to members of Kngwarrayās family, during consultations at the womenās camp in March 2023, they explained that the work encompasses the life cycle of the anwerlarr and its kam. The density and colour of the marks document the age of the plant, from its initial growth to maturity. As Kngwarrayās family described it, the white marks are ampa akely (babies), yellow are awenk (teenage girls) and the brown ones arelh ampwa (old women).

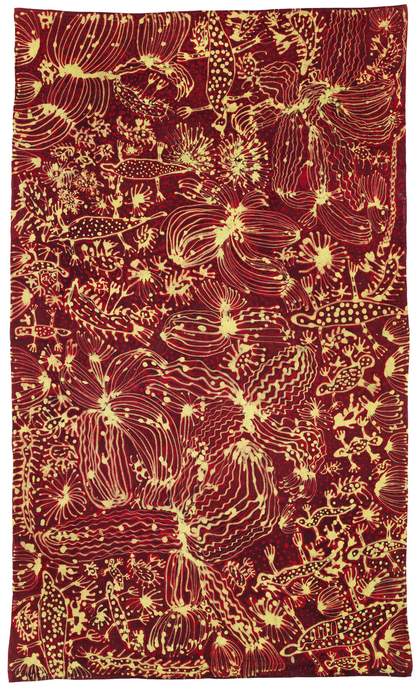

In the many vibrant batik works that Kngwarray produced over a decade, she continued to lay out the groundwork of her Country. Literally drawn into the frame of some of these works on cotton and silk are key emblematic references to the flora and fauna of her Country, as well as her identity as a woman from Alhalker. In an untitled textile work of 1981, mirrored, trailing lines are linked by a bulbous node and cast delicate webs, suggesting both the above-ground and underground plant growth of anwerlarr and kam. Here, too, are other creatures of Alhalker, including centipedes, lizards and emus, all etched in gold against the dyed deep reds resonant of desert sand. The opportunity to document and share the beauty and power of her Country in a new medium and for new audiences seems to have inspired the fulsomeness of the subject matter Kngwarray depicted in her early batik works.

Emily Kam Kngwarray

Untitled 1981

Ā© Emily Kam Kngwarray / Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2025. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2018. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Australiaās digital team

Kngwarrayās first painting, Emu Woman 1988ā9, was created for the landmark group collection A summer project: Utopia womenās paintings. The presence of ankerr (emus) is apparent in the first few years of Kngwarrayās painting works. The prominence afforded to the subject matter by Kngwarray in Emu Woman reflects the special role of ankerr as one of the main themes in Alhalker songs connected to awely (womenās ceremonial traditions including body painting). In Anmatyerr culture the respect accorded to emus is reflected in the rich and extensive lexicon of terms that are exclusively applied to them. These words were recalled by the women from Kngwarrayās family at Utopia Art Centre as, 35 years on from the creation of Emu Woman, they reflected on the iconographies of the work.

In 1989, the National Gallery of Australia acquired Kngwarrayās Ntang Dreaming 1989, which bears the hallmarks of its predecessor Emu Woman in style and execution. At that moment, the rapid ascendancy of Kngwarray as a painter of national significance was confirmed. As interest in Kngwarrayās work grew, the egalitarian model of representative community projects gave way to solo exhibitions.

Kngwarrayās first solo exhibitions mark a time when private commercial interests eclipsed government-sponsored agencies in the marketing and promotion of Aboriginal art. The heightened international interest in Aboriginal art following the 1988 Bicentenary of Australia was no doubt a factor in the growing market. Local Northern Territory cattle or sheep station owners diversified their interests to take advantage of the creative talents of local artists, including Kngwarray. Other individuals, who had previously worked for government arts agencies, established their own dealerships. Independent entrepreneurs of diverse backgrounds entered the fray, fostering a system of opaque accountability that took advantage of the inexperience of artists and the poor socio-economic status of their communities. Meanwhile, Aboriginal-owned art centres, such as Papunya Tula Artists, established by communities in the political era of self-determination from the early 1970s, maintained their collective focus and struggled to protect the interests of their constituent artists amid the growing commercial appetite for Central Australian desert art.

Largely due to the competing and rapacious demands of private art dealers, it wasnāt until 1999 that stable community art centres were able to be established in the Sandover region with the support of the peak Aboriginal art-centre body, Desart: firstly in 1999, Artists of Ampilatwatja in Amperlatwaty (Ampilatwatja), and more recently in 2020, Utopia Art Centre at Arlparra (New Store).

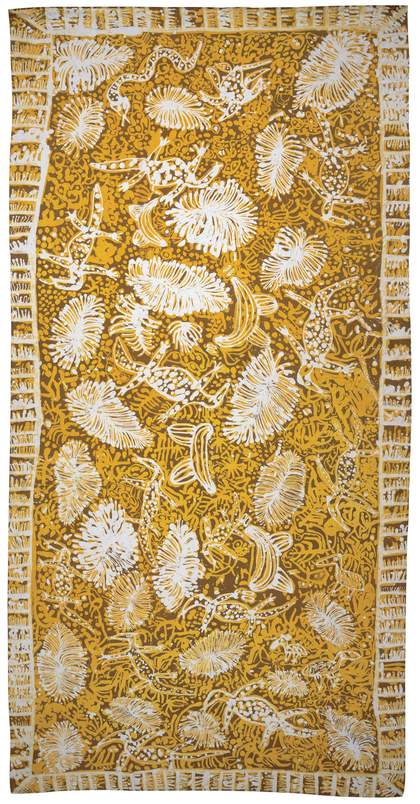

Emily Kam Kngwarray

Emu Dreaming 1988

Ā© Emily Kam Kngwarray / Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2025. Janet Holmes aĢ Court Collection, Boorloo/Perth. Photo courtesy of Janet Holmes aĢ Court Collection, Boorloo/Perth

Within the context of a flourishing, and often unethical, commercial Aboriginal arts sector, Kngwarray continued to confound and stimulate audiences in Australia as well as around the world. Her style evolved rapidly as she repeatedly tapped the deep wellspring of culture and creativity that is Alhalker Country. For instance, the stippled works made between 1990 and 1991 are enlarged and elongated in comparison to earlier paintings. Within these elegant paintings, distinctive motifs such as the anwerlarr tubers and emu footprints are submerged or disappear completely in favour of billowing fields of dots that expand or contract across the surface of the canvas.

In Ntang 1990, the seeds of woollybutt grass are depicted as a dense layering of cream, brown, green, and pale orange dots. This vibrant surface is built upon a linear underlayer, creating a sense of dynamic energy. The oscillating pinpoints of colour in Ntang Altyerr 1990 evoke the profusion of seeds, while larger, pixelated dotting evokes their blossoms, marking a time of seasonal change when pink, purple, yellow and white flowers carpet the contours of Alhalker Country.

The gesture and texture of the application of paint in these works owes much to awely, the hand-painting of ochre onto the body for womenās ceremonies, and the repeated rhythm of song verses, as well as the techniques and styles of womenās sand drawing in the Sandover region, which appear to carry over into acrylic painting. The fluency and rapidity with which the designs are drawn in the sand and then erased to tell the next part of the story, as well as the seated position from which the work is created, bring to mind archival documentation of Kngwarray engaged in the act of painting.

The density of the dotting in the works of Kngwarrayās middle painting years is also reminiscent of sand drawing techniques, where the tips of the fingers leave multiple small, circular indentations in the sand to represent collections of things such as bush foods.

Emily Kam Kngwarray

Ntang Dreaming 1989

Ā© Emily Kam Kngwarray / Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2025. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1989. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Australiaās digital team

Between 1989 and 1996, Kngwarray decisively broadened the colour spectrum and techniques in her works. The most ambitious work of this era is the 22-panel opus entitled The Alhalker Suite 1993, its scale and title implying a kaleidoscopic view of Alhalker. From the intimate perspective of its creator, it is perhaps more accurately a multifaceted portrait of a sentient land. It can be imagined that the painting offers an aerial perspective of winding waterways and changing topographies, all condensed within a work that collectively conveys an intense gravitational energy. Through the eyes of Kngwarrayās countrywomen, the high-keyed colour palette captures seasonal change and the shifting light over a timeless land.

In works made in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the artistās focus appears to shift from foregrounding specific elements to evoking the Country or habitats of ancestral animals and plants. In My Country 1993, billowing clouds of colour and winding traceries are punctuated by a singular section of fine, black dotting around a central roundel. Here, according to the family, Kngwarray had painted Alharlernternerrek, the cave at Alhalker. Understanding the artistās choice of colour is a vital interpretative tool for descendants of the artist since each colour has specific associations with particular plants, animals, places and the passage of time ā seasons, ages, or times of day and night. Batiks and paintings with floral motifs rendered in strong yellow tones can indicate the dried-out vines and leaves of anwerlarr. In addition, for family, the presence of varying hues of green in works such as Untitled 1993 indicates the theme of ankerr with obvious reference to the green colour of emu eggs.

In 1993, Kngwarray made an abrupt about-turn ā stylistically, if not thematically. A suite of works of boldly emblazoned black lines on white paper announced a new and prolific, if short-lived, period of imagery. A plethora of striped works followed, ranging from monochrome to the familiar reds and yellows and bright pops of colour. Their power does not rely on a narrative or literal reading but rather the pulse that emanates from the raw gesture and repetition of the linear mark.

The subject or intention of Kngwarray in creating the linear works is commonly attributed to scarification, the making of small cuts to obtain blood, which helps to heal grief and mourning ā known in Anmatyerr as amarr and awely body designs. Indeed, the paintings exhibit a tactile resonance, as if the acrylic is ochre applied by the fingers following the contours of the body, or sand drawings mapping an infinite cultural landscape. Untitled (awely) 1994 features lines of deep navy converging and connecting to evoke the contours of ridges rising from the plains. Their organic dimension is suggestive of the growth of tubers or of the petroglyphs and engravings found throughout the region, made by the reiteration of a honing action over millennia. The angular, geometric forms that distinguish some works of this period also mirror the pattern of anwerlarr vines and the grid-like intersections of rock incisions. Kngwarrayās works are invocations of the sentience of Country, and of its flora and fauna, channelling the cultural current that derives from the Altyerr.

Emily Kam Kngwarray

Anwerlarr ā my story 1991

Ā© Emily Kam Kngwarray / Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2025. McMahon Family Collection. Photo courtesy of DāLan Contemporary, Naarm/Narrm/Melbourne & New York

In the iconography contained in her early composite batik works, Kngwarray revealed the group of glyphs ā dots, striae, grids and meanders ā that comprise her artistic alphabet. A series of striped works from 1994 capture this idea of the āpulling apartā of layers. These works, loosely documented as awely or body marking, demonstrate an aesthetic approach in which precision appears to be forfeited for texture.

The non-referential nature of these works suggests that they are more about what the act of painting can express: that it is more about the means than the end. Despite her faltering eyesight, the celebrated senior Pintupi artist, the late Makinti Napanangka, continued to paint compulsively, sometimes exceeding the bounds of the canvas laid flat in the studio at Walungurru/Kintore and painting the concrete floor. Observing Napanangka and other elderly desert artists, such as those working at Wanarn in the Ngaanyatjarra lands, it appears evident that the meaning or purpose of a painting for the artist is expressed in the act of its creation. It was remarked by those who witnessed Kngwarray painting that once the work was completed with her characteristic creative confidence and gusto, she would often put down her brush and return home with only a cursory glance at the finished painting.

Kngwarrayās journey is an epic story of 20th-century Australia ā from her birth at Alhalker and experience of the colonial frontier as a young girl, to a lifetime of cultural stewardship and galvanisation of the imagination of the international art world.

In March 2023, Kngwarrayās female descendants camped in Alhalker Country to dance and sing the awely for their Country. At one point, the women summoned a computer with a copy of a 40-year-old archival recording of Kngwarrayās songs and a small portable speaker so that they could listen to and check the sequence and texts of the Alhalker songs. Interjections between verses by Kngwarray, remarking on Alhalker Country or noting the age of these cultural practices, were echoed and affirmed by those gathered. āThis is how the olden time people sang and danced,ā Kngwarray said, before taking up the song again. In the awely performance that followed, Kngwarrayās strong and steady voice provided an accompaniment, transported across time. It was a privilege to witness the presence of Kngwarray, in spirit and in voice, with her countrywomen at this sacred place as they danced and sang what felt like a memorial to their āfamousā family member. And so, the final word on this great artist must be given to her descendants, the contemporary custodians of Alhalker who follow in her footsteps. They simply describe her art as arraty ilem ā telling the truth.

Emily Kam Kngwarray

The Alhalker Suite 1993

Ā© Emily Kam Kngwarray / Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2025. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1993. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Australiaās digital team

Emily Kam Kngwarray at É«æŲ“«Ć½, 15 July 2025 ā 13 January 2026.

Kelli Cole is a Warumungu and Luritja woman from Central Australia and is Director of Curatorial and Engagement, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Gallery of Australia. Hetti Perkins is an Arrernte and Kalkadoon curator, writer, advisor and presenter. A longer version of this article appears in Emily Kam Kngwarray, published by National Gallery of Australia and Tate Publishing.

Emily Kam Kngwarray is presented in The Eyal Ofer Galleries. In partnership with the National Gallery of Australia and Wesfarmers Arts. Further lead support from Fondation Opale. With additional support from Bloomberg Philanthropies, The Emily Kam Kngwarray Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons, Tate Americas Foundation, National Gallery of Australia Foundation and Tate Members. Research supported

by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor. Exhibition organised by É«æŲ“«Ć½ and the National Gallery of Australia based on an exhibition curated by Kelli Cole, Warumungu and Luritja peoples and Hetti Perkins, Arrernte and Kalkadoon peoples.