Onyeka Igwe with work in progress for her Art Now exhibition at her studio in Somerset House, London. Photos for Tate Etc. by Kwame Dapaa, assisted by Lollie-Alexi Ipinson- Fleming, July 2025

┬® Kwame Dapaa

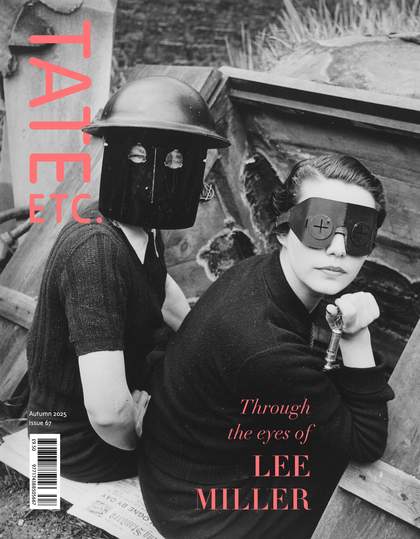

Despite destabilising the stories we take to be true, Onyeka IgweŌĆÖs films and installations elicit a sense of freedom. The London-born artist mixes analogue and digital film, and collaborates with composers to build distinctive sound scores in immersive installations. Her exhibitions create moments of possibility in which we are asked to reconsider the lasting structural hold of empire.

IgweŌĆÖs relationship to research and archives is unconventional, insofar as she does not attempt to articulate hard facts from what she finds. Instead, her experimental documentaries play with the form ŌĆō of film, history, truth ŌĆō by reconstituting notes, gestures, images and stories into other, possible worlds. In this way, her work explores how truth and knowledge are constructed. ŌĆśFact is a question of powerŌĆÖ, she says. ŌĆśTruth is a question of power.ŌĆÖ

For her new Art Now exhibition at Tate Britain, Igwe has produced and directed a film on site at the University of Ibadan in Nigeria. Of course, presenting any project at Tate comes with its own unique associations. ŌĆśNot just its links to colonial history through the Tate & Lyle sugar company, but even the vast architecture of the building itself ŌĆÖ, she tells me, although the weight of expectation has also clearly been galvanising: ŌĆśI tell my mum IŌĆÖm showing there and she understands precisely what that signifies, which means a lot. So I wanted to make something ambitious. I wanted to make something that feels like the articulation of everything IŌĆÖm interested in in this present moment, on a big scale.ŌĆÖ

Yaniya Lee, June 2025

YANIYA LEE You recently published a book about the June Givanni PanAfrican Cinema Archive, a collection of films and archival material related to Pan-African and Black British cinema. As a social and political movement, Pan-Africanism supports the liberation of people of African descent, as a sort of unified diaspora. Pan-Africanism has also been a central theme in your own research and recent work. What draws you to it?

ONYEKA IGWE Pan-Africanism isnŌĆÖt something I would have thought about as being central to my work even five years ago, but engaging with JuneŌĆÖs archive probably opened me up to a more expansive understanding of it. The Pan-Africanism that the archive reflects is about liberation and alternative ways of organising the way we live and the world we are in. So, Pan-Africanism becomes a way of thinking beyond borders and nations. ItŌĆÖs not necessarily exclusively related to people living in Africa but is more about the thought and politics that have been produced by people on the African continent and its diaspora. ItŌĆÖs an alternative mode to Western colonialism; one example of another route.

My work has increasingly become engaged with these ideas because IŌĆÖm interested in other ways of knowing. There is more to how we know ourselves ŌĆō how we know each other, how we know the world ŌĆō than the way I was taught to know about those things from a Western, white European, scientific perspective. Like most people, IŌĆÖve always lived with more than one approach to the world. All my family are from Nigeria, which means that this other culture has always been present in my life. I often think about how, when my brother and sister and I used to play rock, paper, scissors as children, we invented an extra option of ŌĆśblack magicŌĆÖ, because when we watched Nollywood films there was so much juju and black magic in those stories that we thought: It must be another category!

Onyeka Igwe with work in progress for her Art Now exhibition at her studio in Somerset House, London. Photos for Tate Etc. by Kwame Dapaa, assisted by Lollie-Alexi Ipinson- Fleming, July 2025

┬® Kwame Dapaa

YL Your upcoming exhibition our generous mother, part of Tate BritainŌĆÖs contemporary Art Now programme, includes the new film Penkelemes. Where did the ideas behind this project stem from?

OI I was inspired to make the film a few years ago, when I went to do some archival research for another film, A Radical Duet (2023), at the University of Ibadan. A couple of hours from Lagos by train, it is the first and oldest university in Nigeria. I grew up hearing stories about it from my mother, who studied there in the 1970s. Her accounts felt like a fairy tale about how she came to be the person who she was.

The university was conceived and came into being in 1948, under British Colonial rule, as an outpost of the University of London. ItŌĆÖs a little campus famed for its tropical modernist architecture. Tropical modernism is a term used to describe some of the work of Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, an architect couple who designed some important buildings in West Africa in the 1940s and 1950s. It was an approach that emerged in the mid-20th century and combined modernist architectural ideas with regional styles and building practices. The coupleŌĆÖs work was distinct for its emphasis on geometry and brise-soleil design features, which screened sunlight and encouraged cross breeze. They were attempting to manage the tropical climate, but I also see their method as a form of paternalistic architecture, which has since been co-opted, morphed and Nigerianised.

YL What were some of the things you learned, in terms of the history of the university and the experience of people who went there? What was your motherŌĆÖs experience, for instance?

OI My mum comes from a small, rural village in southeastern Nigeria and she was the only person in her family to go to university, and one of the few to even finish secondary school. Her journey from the countryside to the best university in the country involved hardship and struggle, jeopardy and drama. It was a tale she would regularly remind me of whenever I couldnŌĆÖt be bothered with school. So, I guess, growing up, the university was in the realm of symbolic fantasy or something. But the University of Ibadan also looms large in the cultural imagination of Nigeria. After independence in 1960, it was the hub of Nigerian art and literature. Many famous writers like Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka attended, while key cultural movements like the Mbari Club started there, as did the literary journal Black Orpheus.

When I was in Nigeria this April, I picked up a novel called Alma mater (1995) by Ola Omiyale, which became key to my understanding that the university experience at Ibadan in the 1950s and 1960s was akin to an American Dream narrative. While on campus, I talked to current students and learnt about the ways in which the university has since declined due to a lack of funding, and also how an active teaching union has meant strikes are now a common feature of education in Nigeria.

For the new film, I interviewed 15 people who were associated with or had attended the university, from the late 1940s to the present day, including 95-year-old Mrs Ade Ajayi, who was around when the university was founded in 1948. Her husband had been a professor there and a renowned member of the Ibadan School of History. Mrs Ajayi told me about the housing in which she had lived on the outskirts of the campus, near the Awba Dam, and about teaching the children of the university staff. There are multiple voices in the narration of the soundtrack: people from the present, archival voices from the 1940s and 1950s, and fictional voices, all of which meld together to tell the story, or their own stories, of this one place.

Onyeka Igwe with work in progress for her Art Now exhibition at her studio in Somerset House, London. Photos for Tate Etc. by Kwame Dapaa, assisted by Lollie-Alexi Ipinson- Fleming, July 2025

┬® Kwame Dapaa

YL So youŌĆÖre mixing fact and fiction?

OI I think a lot of my films play with what is true, or fact, and what is a story. But I donŌĆÖt think that singular truth is a real thing. I think the truth is a question of power. Fact is a question of power. And many things can be true at the same time. I donŌĆÖt mean this in a conspiracy theory kind of way, but I think all my films use that central premise. I made a film called the names have changed, including my own and truths have been altered (2019) and that title really gives it all away. It was this idea of multiplicity: How can we present the same story in many different ways and using many different narrative tools?

The film that IŌĆÖve made for Art Now is a sister project of this film, because, again, it is trying to understand one place ŌĆō the University of Ibadan ŌĆō in all its multiplicity. This time, that involves many peopleŌĆÖs stories of the same place being given equal standing. And also thinking about the fragment and the whole. The way the film is constructed resonates with the title, Penkelemes, which comes from the subtitle of Wole SoyinkaŌĆÖs memoir of his time at the university. It is a Yoruba word that derives from the phrase ŌĆśpeculiar messŌĆÖ, which had been used to describe political disorder in the colonial years.

YL You mentioned youŌĆÖre thinking about the fragment and the whole. How does this play out in the exhibition?

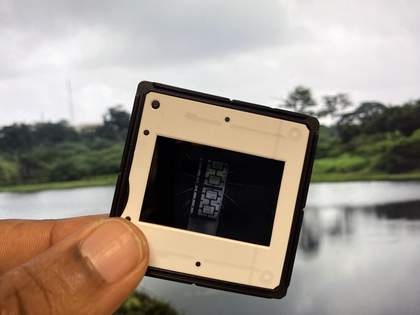

OI Penkelemes is a two-screen work, but youŌĆÖre not able to see those two screens at the same time: theyŌĆÖre projected on walls that face one another. Entering the gallery, youŌĆÖll first encounter the film projected through a reflective and refractive sculpture made of Perspex and based on a brise-soleil design taken from the architecture of the university, which fragments the image. Then, as you move through the space, you experience the film in two parts: one screen shows a slide projection of an imagined archival film, and the other is a digital video projection of recently shot material. ItŌĆÖs all one film brought together by a spatialised soundtrack, but, being split up in this way, itŌĆÖs not possible to view the whole work at once or from any single place. The film is presented as visual fragments across the space of the exhibition.

YL How did you find the experience of shooting the film in Nigeria this spring?

OI I was in Nigeria for about two weeks and worked with a mostly Nigerian crew, who were based in Lagos and Ibadan. We were about 11 people in total. Everyone was local ŌĆō including a great director of photography, Granville Wilson, and a producer, OD Odeyotin. The only exception was a friend called Xavier Pillai, who came from the UK to work on photography, sound and research.

Both the still photography and film elements of the project were shot on a mixture of digital and analogue technology. We rigged the camera on little kekes [rickshaws] and drove around the whole campus. We also shot on slide film and recorded a bunch of field recordings on location, in between interviews.

Onyeka Igwe with work in progress for her Art Now exhibition at her studio in Somerset House, London. Photos for Tate Etc. by Kwame Dapaa, assisted by Lollie-Alexi Ipinson- Fleming, July 2025

┬® Kwame Dapaa

YL Why do you like to combine different digital and analogue film media in this way?

OI I have always mixed video or film media in my work. From the earliest things that I made, 10 years ago, itŌĆÖs been a bit of VHS, MiniDV, digital, and 16mm or Super 8mm. I quite like the mix, and donŌĆÖt enjoy an aesthetic that is too samey. I also find analogue technology fascinating and magic, and want to learn more about it. IŌĆÖm not incredibly technical or a super-geek about these things, but I am curious. I like to experiment.

YL YouŌĆÖre making me realise that every medium is so era-specific. As our technologies have progressed ŌĆō from the 1960s, film cameras became portable and anyone could own them ŌĆō the aesthetic of the medium will tell you what time youŌĆÖre in. Something from the 1980s, like VHS, has a distinct look and feel, while a MiniDV from the 1990s will also have its own aesthetics, and so on. To play with media can become this funny form of time travel.

OI What I find interesting about cinema is that the medium itself is time. You get to play around with it, and you can put lots of different things in the container of that frame ŌĆō sound, music, performance, photography ŌĆō and then time acts upon it.

So yes, youŌĆÖre right, different media signal different eras. And the ways in which we understand images, and the frequency with which we see images, means that we can be led down certain paths quite quickly, with hints from the use of specific media. I like to play in that terrain.

Onyeka Igwe with work in progress for her Art Now exhibition at her studio in Somerset House, London. Photos for Tate Etc. by Kwame Dapaa, assisted by Lollie-Alexi Ipinson- Fleming, July 2025

┬® Kwame Dapaa

YL You said once, in another interview, that you see a link between the medium of cinema and colonialism. Can you elaborate on what you meant by this?

OI The emergence of cinema as a medium and form of entertainment happened at a key moment in colonial history. Photography and cinema were co-opted, along with the development of anthropology as a scientific (or academic) discipline, as tools to prove as true the central tenets of colonialism ŌĆō that particular races were inferior to others. I previously researched films by the Colonial Film Unit, which made instructional films as ŌĆścivilisingŌĆÖ and propaganda tools in the early 20th century. Of course, things have moved on since then, but that original DNA, what the medium was initially used for, still resides in cinema. There is an idea of cinema as visual evidence, and also as an aspirational place for imagination to become real ŌĆō to become truth or fact, in celluloid. So, I think itŌĆÖs a powerful and dangerous medium, but one that, because of and despite this, has a lot of scope and potential. And thatŌĆÖs exciting.

YL How, then, do you use this medium, as a filmmaker, knowing that this history is embedded in it?

OI IŌĆÖve always been deeply fascinated and compelled by construction. And I think in cinema, in the process of construction, things can become real. That is magic. I feel it strongly in editing ŌĆō there is something so libidinal about the experience of editing. You have these images, all these little parts, and you can make them into one whole film. You can make them into whatever you want! You can feel when it works, getting closer to being the thing that you need it to be. When IŌĆÖm editing, itŌĆÖs such a maddening, desperate and exciting moment, because all of that is happening at once.

I think what IŌĆÖm trying to do with cinema is to make something real, and what IŌĆÖm trying to make real are ideas, notions, things that I have questions about. Things that I notice in the world, that I want to try out, and that I think are important for other people to understand, so we can talk about them more.

Onyeka Igwe with work in progress for her Art Now exhibition at her studio in Somerset House, London. Photos for Tate Etc. by Kwame Dapaa, assisted by Lollie-Alexi Ipinson- Fleming, July 2025

┬® Kwame Dapaa

YL Your interest in how things are made seems tied to how truth, as knowledge, is made. What I mean to say is, your material investigations within film have a double in the theoretical construction of truth within reality.

OI I think youŌĆÖre right, and I think a lot of these things stem from my background in political science. I read people like Michel Foucault and his theory that society is made up of discourses, of things you can and cannot say within a particular period at a particular time, and how those things are changeable. For a long time, IŌĆÖve been very invested in the world changing, and the idea that things are changeable is such a permission, is such a gift. To be able to say, ŌĆśOK, this is not rigid. The way in which the world is now doesnŌĆÖt always have to be the case.ŌĆÖ

Later, I came across Sylvia Wynter, who says something similar: ŌĆśWe can change our reality.ŌĆÖ The method we use to change reality is to first understand how things come to be. Because once you see that, then you can understand how things could be made differently. I remember learning about these theories of other possible worlds and being very convinced by them. I thought: ŌĆśYes! There are many possible ways. Everything is contingent. It could have been so different.ŌĆÖ And so, in many ways, cinema is just a way of making possible worlds.

Art Now: Onyeka Igwe, Tate Britain, 19 September 2025 ŌĆō 17 May 2026.

Onyeka Igwe is an artist who lives and works in London. Yaniya Lee is a writer based in Berlin. Kwame Dapaa is a photographer based between Manchester and London.

Supported by the Bukhman Foundation. With additional support from the Art Now Supporters Circle and Tate Americas Foundation.