Pablo Picasso painting a figure with light in a long-exposure photograph taken by Gjon Mili in Vallauris, France, 1949

Gjon Mili/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

ãFor I is an other.ã

- Arthur Rimbaud, Lettre du Voyant, 1871

Pablo Picasso once admitted to fellow artist Brassaû₤, as recorded in his Conversations with Picasso (1964): 'Why do you think I date everything I make? It's because it's not enough to know an artist's works. One must also know when he made them, why, how, under what circumstances'.

ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs The Three Dancers 1925 is one of the most famous works in ¯íý¿°ìÝÞãs collection, and has long been the subject of curatorial research ã from speculations about the paintingãs background and the real people it might represent to the choreography that inspired the artist. This year, ¯íý¿°ìÝÞãs groundbreaking exhibition Theatre Picasso, devised by contemporary artist Wu Tsang and author and curator Enrique Fuenteblanca, uses ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs own engagement with performativity as a lens through which to restage a wide selection of his works from the collection and beyond.

One hundred years after The Three Dancersã creation, the exhibition presents a new opportunity for Tate to delve deeper into the workãs provenance and history. During our recent archival research at Museäe national Picasso-Paris (MPP), a previously unexplored 19-year period of the workãs history, between 1939 and 1958, resurfaced, reshaping both how we see the work, and how we can understand its place within a much broader transnational art-historical context.

Tate Gallery director Norman Reid, curator Philip Hendy and Roland Penrose inspect ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs The Three Dancers upon its arrival to the gallery on 24 February 1965

Photo by Stan Meagher/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

When The Three Dancers entered Tate Galleryãs holdings in 1965, it already had a hint of notoriety. The acquisition was hailed as important and transformative on the one hand, and criticised as a waste of public money on the other. During the acquisition, which was mediated by ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs friend and fellow artist Roland Penrose, ¯íý¿°ìÝÞãs first curatorial report on the work hailed the canvas as ãa masterpieceã, noting its ãspecial personal value to the artistã and the importance of seeing it through the prism of ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs ãdevelopment and his lifeã ã namely, the artistãs work for the dance company Ballets Russes, personal trauma, and the paintingãs relevance to the surrealist cause. Subsequent Tate literature on the subject followed in the same vein, sustaining a reading of The Three Dancers as one of the works that Picasso held close throughout his life.

The Three Dancers depicts a room in which three figures shift, perform and transform against the backdrop of an open window. Recent conservation research revealed that over the course of the first six months of 1925 the composition underwent a number of changes ã from traditional to playful to provocative. The multilayered composition was executed in stages, beginning with three figures in grisaille, over which Picasso painted the classical forms of female dancers. Then, an expressive reworking took ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs artistic exploration of dissonance and constraint within bodily freedom to another level.

These changes reflected the transition that the artist himself was undergoing. The year 1925, in which The Three Dancers was made, marked a significant turning point in ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs life and work. In the period leading up to the paintingãs execution, he had begun to move away from the ballet world, which had offered him both wider public acclaim and financial security. His final major work for the stage was not for Ballets Russes, with which he had become famously associated, but rather the rival enterprise of Count Eätienne de Beaumont, a Parisian socialite and patron of the arts. The ballet Mercure (1924) was an experimental project that celebrated the nonsensical and transgressive through disruptive interactions. Choreographed by Leäonide Massine, the project was designed and staged by Picasso, and activated by Erik Satieãs music and lighting design by the American dancer Loie Fuller.

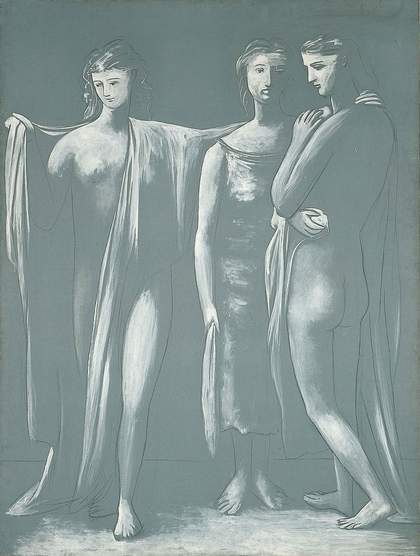

The composition of The Three Dancers is often associated with one of the tableaux from the Mercure production, constructed around the interactions between the mythological figures of the Three Graces. In the theatre scene set by Picasso, three male performers ã crossdressed and adorned with female attributes crudely crafted from cardboard ã engage in subversive gestural play on stage. Through this provocative scene, Picasso exorcised the residual reverence for the classical canon that had dominated his oeuvre in the early 1920s, such as his monumen- tal neoclassical painting The Three Graces, commissioned by de Beaumont and executed in grisaille in 1923.

Pablo Picasso

The Three Graces 1923

ôˋ Succession Picasso/DACS 2025. Image ôˋ Fundacioän Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, Madrid / Museo Picasso Maälaga. Photo: Marc Domage

The focus of art-historical research on The Three Dancers has not been limited to ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs work on the production of Mercure and his composition for The Three Graces. Generations of academics and museum curators have also investigated the identities of the characters depicted in the painting.

A single comment by Picasso in 1965, during a conversation with Penrose just before the painting was sold to Tate, triggered a chain of art-historical interpretations linking the three figures to people close to Picasso during his formative years in Paris. Picasso stated that the painting should have been called ãThe Death of Pichotã, since he had learned of the passing of his friend, fellow Catalan artist Ramon Pichot in March 1925, while working on this painting. Consequently, the shadow figure on the right is interpreted as being that of his deceased companion.

The contorted shape of the dancer on the left is thought to be that of Germaine Gargallo. In her youth, she had been the target of unwanted interest and a murder-suicide attempt by the artist Carles Casagemas, a mutual friend of Picasso and Pichot. Such a reading imposed a misogynistic interpretation onto the figure, imbuing it with aggressive female sexuality. More frequently, it is read as the representation of another significant person in ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs life ã Olga Khokhlova, his first wife and a former dancer with the Ballets Russes.

As T.J. Clark remarks in his book Picasso and Truth (2013), the workãs composition is unique within the artistãs oeuvre, though its setting in the confines of a room is similar to that of his large-scale still life paintings from the summer of 1924 (such as Mando- lin and Guitar). However, the suggested drama of the inanimate, yet symbolically rich, objects is replaced by the human drama that unfolds as a spectacle of death. Thus, the painting has been interpreted as a reflection of ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs ongoing interrogation of bodily truth, and his increasing discomfort with conventional representations of harmony or beauty.

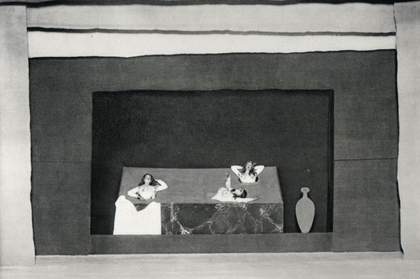

ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs set design for the Three Gracesã bathing scene in the ballet Mercure (1924)

ôˋ Succession Picasso/DACS 2025. Paris, museäe national Picasso-Paris. Photo ôˋ GrandPalaisRmn (museäe national Picasso-Paris) / Micheäle Bellot

Our recent archival research around The Three Dancers has also allowed us to look beyond the given provenance of the painting. While it remained the artistãs legal property, it was seen solely as ãÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs Picassoã. Retracing the workãs transatlantic journey, however, reveals a more complex story.

On 21 July 1939, the SS Iäle de France arrived in New York carrying The Three Dancers, along with other paintings from ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs private collection. These were destined for his first retrospective exhibition in the United States ã Picasso: Forty Years of His Art, at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. As the Second World War engulfed Europe, the exhibition solidified the artistãs reputation in the Americas.

While the paintingãs arrival for the 1939 MoMA show is well-documented, the subsequent 19 years of its exhibition and display history have largely been overlooked by art historians. This could be explained by ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs own careful choreography of the production, display and interpretation of his work. This approach predetermined how his studio output was viewed and understood by the public and specialists alike.

A copy of the MoMA report found at MPPãs archives charts The Three Dancersã detailed US history of circulation, from its arrival in 1939 until its return on 6 March 1958. The report lists exhibitions and displays that the work appeared in during the Second World War years and beyond ã from museum collection displays to touring shows.

Pablo Picasso

Mandolin and Guitar 1924

ôˋ Succession Picasso/DACS 2025. Image ôˋ The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation/Art Resource, NY/Scala, Florence

In April 1941, the status of the works from ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs collection changed from ãexhibition loansã to ãwar loansã. This allowed legal guardianship of the paintings that otherwise would have been returned to Nazi-occupied France. The works were safe from looting and destruction while cared for and displayed in a museum collection.

Understanding that The Three Dancers ã along with Guernica 1937 and other loans from the artistãs own collection ã remained at MoMA years after the end of the war, changes the traditional view of its legacy and transnational impact. The painting had been incorporated into MoMAãs displays and exhibitions, viewed on its own or alongside other celebrated paintings by Picasso such as Les Demoiselles dãAvignon 1907. It was shown in monographic shows and contrasted with the most recent works created by the new generation of artists in the Americas, such as Jackson Pollockãs Mural 1943, and Roberto Mattaãs Being With 1946.

It underwent restoration in 1943, colour reproduction at a photoengraving studio, and was published in colour for the first time in The Tigerãs Eye magazine in 1948. On multiple occasions it was displayed in the museumãs entrance areas to be viewed by arriving visitors, and it was experienced by the wider public through touring exhibitions in the 1950s, travelling to Toronto, Saäo Paulo and beyond.

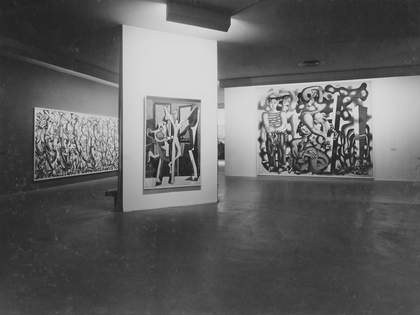

These shows offered fresh context for the work. MoMAãs 1947 exhibition Large-Scale Modern Paintings, for instance, brought to the fore the idea that the paintingãs multilayered structure was an attempt by Picasso to approach painting as a gestural act ã one that conveyed the artistãs inner state and struggles. The exhibition also emphasised how larger formats and boldness of composition could enhance both the emotional intensity of the work and a viewerãs immersion in it. Crucially, the exhibition also included works by Latin American artists David Alfaro Siqueiros (Mexico), Roberto Matta (Chile) and Rafael Moreno and Wifredo Lam (Cuba), signalling the expanding global perspective of the post-war era.

Installation view of the exhibition Large-Scale Modern Paintings at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, AprilãMay 1947, showing ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs The Three Dancers 1925 alongside Jackson Pollockãs Mural 1943 (left) and Fernand Leägerãs Composition with Two Parrots 1935ã9 (right)

Photo: Soichi Sunami (ôˋ The Museum Of Modern Art, New York). Image ôˋ The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

Those links, juxtapositions and encounters provide valuable insight into the development of modernist tendencies as the Americas emerged as new centres of artistic thought, investigation and production. Such positioning ã with Siqueirosãs expression of social conscience and Mattaãs cosmic surrealism ã reveals how the use of scale was deployed to dramatise upheaval, situating the 1925 canvas as a link across nations, generations and artistic affiliations, in modern artãs evolving language of monumentality.

Viewing the work in this wider, global context, and positioning The Three Dancers outside the usual art-historical narrative and ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs own control, opens up the possibility of multiple viewpoints, connections and encounters across geographies and generations. While Picasso, with his life trajectory, is saying ãIã, his art, following the words of the poet Arthur Rimbaud, is clarifying: ãI is an otherã.

With the new exhibition Theatre Picasso at 訢ÄǨû§, there is an opportunity to consider The Three Dancers afresh. The new approach to its research allows for a more nuanced and complex narrative, one centred around broader histories of institutional collecting, art economies and artistic strategies of image- and myth-making. Ultimately, this new information enriches the story of one of ÝòƒÝ°Îý¿ý¾ý¾Çúãs key works, underscoring how lauded collection ãmasterpiecesã can yield new insights, reminding us of the fluid and evolving nature of art history.

Pablo Picasso, The Three Dancers 1925

Tate. ôˋ Succession Picasso / DACS 2024

Theatre Picasso, 訢ÄǨû§, 17 September 2025 ã 12 April 2026.

Natalia Sidlina is Curator, International Art, 訢ÄǨû§.

Presented in The George Economou Gallery. In partnership with White & Case. Also supported by the Huo Family Foundation. With additional support from the Theatre Picasso Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation and Tate Members.