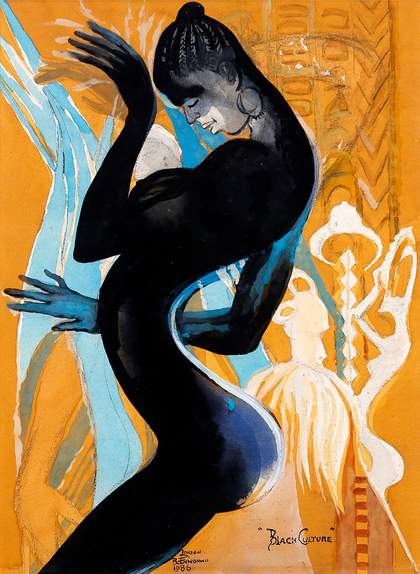

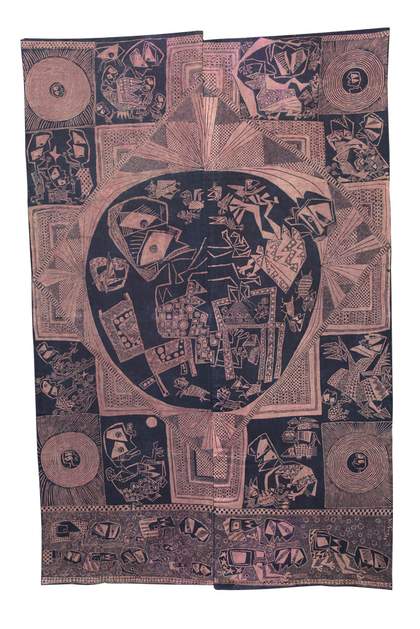

Nike Davies-Okundaye

The Palmwine Tapper and Ayo Game 1969ŌĆō70

┬® Nike Davies-Okundaye. Photo courtesy of ko╠ü, Lagos

In the lines that follow, I hope to record my thoughts and feelings on the history of modern art in Nigeria, in a way that retains some sense of wonder for a non-expert like myself. I am self-educated in Nigerian art history, which is also likely the case for nine out of ten readers of these words. My propositions can only hint at the myriad stories ŌĆō of diverse approaches to art, of international artistic networks, and of social and political revolution ŌĆō that this exhibition seeks to bring to the surface. Perhaps, though, we ought to think of art criticism as less a source of answers than an accompaniment to artworks, leading the reader towards their own ideas. In this sense, assume that I have cut a partial, and impressionistic, path through this history, whose riches I hope you will be encouraged to seek out for yourself.

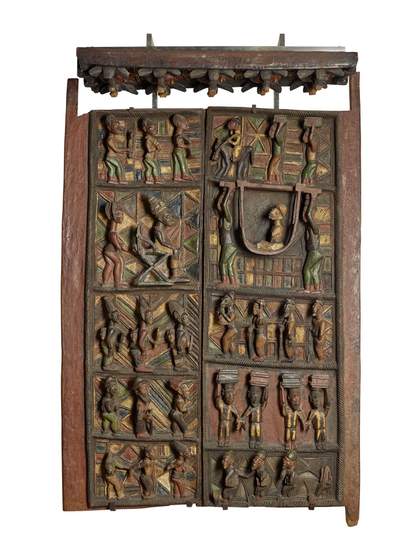

Aina Onabolu

Portrait of an African Man 1955

┬® Estate of Aina Onabolu. Photo courtesy of Yemisi Shyllon Museum of Art, Pan-Atlantic University

In 1920, the artist Aina Onabolu (1882ŌĆō1963) wrote A Short Discourse on Art. He was 38 years old and nearing the midpoint of his life. At 38, you are old enough to think of youth as a terrain to which youŌĆÖre acclimatised. You are also old enough to have found a perch of experience from which you can speak to those who are far younger than you. Onabolu was by then a renowned portrait painter in Nigeria, but notably, in a prefatory remark in a copy of the pamphlet I recently found online, readers are given a London address should they wish to contact him: ŌĆśAina Onabolu, C/o Principal, St. Johns Wood Art Schools, 29 Elm Tree Road, London N.W.S.ŌĆÖ Which is to say that, while in possession of a secure reputation as a self-taught artist in Nigeria, he nonetheless decided to journey to London to receive a formal education in art.

░┐▓į▓╣▓·┤Ū▒¶│▄ŌĆÖs A Short Discourse on Art is generally accepted as being NigeriaŌĆÖs first piece of art criticism. The essay has its origins as a catalogue text, published to accompany an exhibition of the artistŌĆÖs paintings, though it says little about his own art. Instead, Onabolu aimed for a broader treatise, a kind of polemic on the dispiriting state of art appreciation and art education in Nigeria at the time. He himself had come of age as a student at a craft school, illustrative of what was deemed fitting for potential fine artists by the then colonial government. His essay is shored up by a general survey of the history of art ŌĆō ŌĆśart advanced and attained its highest perfection in ancient GreeceŌĆÖ ŌĆō and ends with a nationalist call to action: ŌĆśYoungmen, let us wake up to duty; on us depends the future of Nigeria.ŌĆÖ

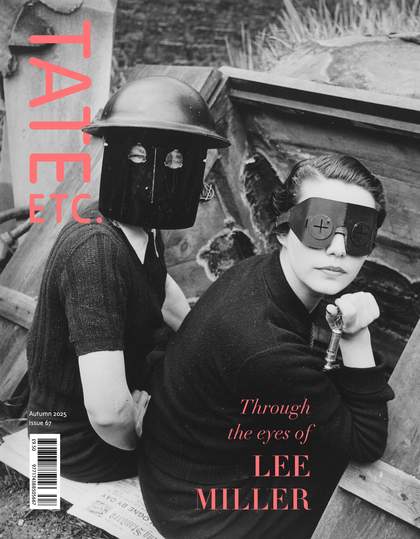

Olowe of Ise

Door │”.1910ŌĆō14

┬® The Trustees of the British Museum, London

There is only one artist represented in the Nigerian Modernism exhibition who was born before Onabolu. Olowe of Ise (c.1873ŌĆōc.1938) took his name from the city where he lived most of his life, though his birthplace was the famed carving centre of Efon-Alaaye in southwestern Nigeria. Since Olowe forwent a personal surname in service of a communityŌĆÖs narrative, it is fitting that the most beloved of OloweŌĆÖs sculptures, Door │”.1910ŌĆō14, reimagines a 1904 encounter between the Ogoga (king) of Ikere and Captain William Ambrose, in which the colonial British official is outnumbered by the Indigenous royal cortege. As art historian Will Rea has pointed out, this monumental carved door would have been placed in a conspicuous entry point in the Ikere palace courtyard to indicate a meeting of equals.

In contrast with OloweŌĆÖs modesty, the later artist Aina Onabolu situated himself as the hero, beginning his Short Discourse: ŌĆśThe object of this picture exhibition is to show to the public in general some of the pictures I have been able to paint without the aid of an Art master...ŌĆÖ And from Onabolu onwards, the work of the Nigerian artist, with some exceptions, appears to be threaded with an attentiveness to individual renown.

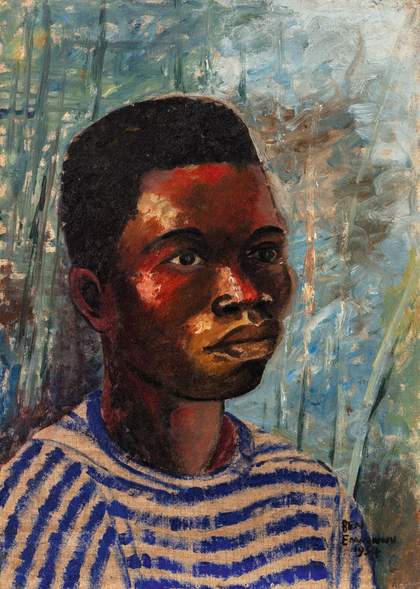

Ben Enwonwu

Portrait of a Young Boy 1954

┬® The Ben Enwonwu Foundation. Private collection. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town, Johannesburg, Amsterdam

Though he both painted and sculpted, Ben Enwonwu (1917ŌĆō1994) preferred to be known as a sculptor, like his father, whose adze (an axe-like carving tool) he used in his studio for all his working life. The first painted portrait Enwonwu made, titled Portrait of a Young Boy 1954, is strikingly similar in composition and perspective to the second, a self-portrait he painted the following year. I know of no other self-portrait by Enwonwu. Besides a few sculptures, there is little further engagement in his work with individual faces as frontispieces of identity. In most of his paintings, the canvas is stretched ŌĆō figuratively speaking ŌĆō to accommodate an assembly of bodies or masquerades, or an expanse of landscape.

Note the distinction between the ceremonial cheer in his crowd scenes ŌĆō or in the dancing figures he repeatedly painted throughout his career ŌĆō and the demure, regal disposition in his 1957 sculpture of Queen Elizabeth II.

Ladi Kwali

Pot undated

┬® Ladi Kwali. Photo courtesy of School of Art Museum and Galleries, Aberystwyth University

The pottery of Ladi Kwali (c.1925ŌĆō1984) is among the least egocentric art produced in 20th-century Nigeria. One way to appreciate the distinction between her ceramic work and, say, the sculptures of Enwonwu or Justus D. Akeredolu (1915ŌĆō1984), who created small wooden figures, is the tendency for her artistic efforts to be regarded simply as the best example of traditional Gwari pottery, in which women used free-handed moulding techniques to create vessels decorated with figures and shapes. These pots, one could argue, were similar in form and function to those made by her forebears, though set apart by her particular talent for firing techniques. She enters the record in a unique position, however: there is no other figure in the history of that period who worked with ceramics as a primary artistic language.

My exploration of her work was ambushed by a detail I came across, which left me with some discomfort. In the 1960s and 1970s, her British teacher, Michael Cardew ŌĆō whose pioneering zeal led to the creation of the Abuja Pottery Training Centre ŌĆō would organise international tours in which Kwali displayed her skills to enthused audiences. Photographs of these events record her talent and meticulousness ŌĆō whether she is shown inspecting a finely turned pot up close or incising a vessel with great attention. Yet I realise there is a distinction between a display of pots, shown as resolved art objects, and the presentation, or performance, of the potter as being highly or unusually skilled. What did those audiences in Europe and America think of her? An artist par excellence or an ethnographic curiosity?

Justus D. Akeredolu

Thorn Carving c.1930s

┬® Justus D. Akeredolu. Photo courtesy of Research and Cultural Collections, University of Birmingham

The period between 9 October 1958, when the Zaria Art Society held its inaugural meeting, and 16 June 1961, when it disbanded (after its members graduated from the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology) signalled an inflection point in Nigerian art history. For the first time, a school of higher education in Nigeria was educating artists ŌĆō teaching them how to make art, and what to make of art. From this institution, a credo of ŌĆśnatural synthesisŌĆÖ flourished, written first as an address by the societyŌĆÖs president, Uche Okeke (1933ŌĆō2016), around the time of NigeriaŌĆÖs declaration of independence in 1960: ŌĆśOur new society calls for a synthesis of old and new, of functional art and art for its own sake.ŌĆÖ

Now that these words have become outsized and multi-generational in their impact ŌĆō and the foundational, oft-cited ethos for ŌĆśa virile school of art with new philosophy of the new ageŌĆÖ, as Okeke put it ŌĆō itŌĆÖs impressive how readily they were adopted as a group tenet. ŌĆśWe must grow with the new Nigeria and work to satisfy her traditional love for art or perish with our colonial pastŌĆÖ, Okeke noted elsewhere. I am reminded of Onabolu, who ŌĆō some 40 years earlier, and in a very different political context ŌĆō also felt that the era required an artistic response or awakening befitting the historical moment: a call for ŌĆśyoung-men to wake up to dutyŌĆÖ. (Notably similar is the first sentence of OkekeŌĆÖs manifesto: ŌĆśYoung artists in a new nation, that is what we are!ŌĆÖ) To be young, to face a horizon of promise, is often to revel in a feeling of indispensability.

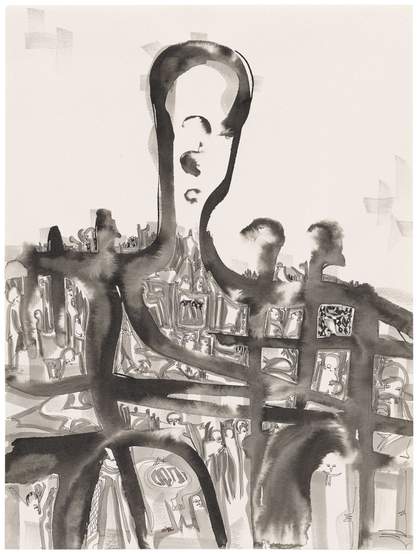

Uche Okeke

Fantasy and Masks c.1960

┬® Uche Okeke, The Prof Uche Okeke Legacy Limited and Asele Institute Ltd/Gte. Photo courtesy of Research and Cultural Collections, University of Birmingham

An artistic highlight of the early 1960s was the Mbari Club, founded by the German cultural impresario Ulli Beier, in the southern cities of first Ibadan, and then Osogbo and Enugu. The club welcomed not just visual artists, but writers too, as was particularly evident in Ibadan. Soon, besides the clubŌĆÖs regular art exhibitions, the magazine Black Orpheus (named after a line in an essay by Jean-Paul Sartre) was founded, becoming a primary outlet for its membersŌĆÖ work and ideas.

Uche Okeke and writer Chinua Achebe were members of the Mbari Club; it was Achebe who gave it its name, and OkekeŌĆÖs paintings, together with those by Demas Nwoko (born 1935), were brought together for the groupŌĆÖs first exhibition. By the time of MbariŌĆÖs founding, AchebeŌĆÖs Things Fall Apart (1958), the novel that made his reputation, had already been published in London. But it seems he wasnŌĆÖt enthused by the illustrations provided by Dennis Carabine for an initial reprint of the book in 1962. In response, he asked Uche Okeke to provide new images for a 1963 edition. When he saw the drawings for the first time, Okeke recalled Achebe saying: ŌĆśThat is how it should be.ŌĆÖ

OkekeŌĆÖs drawings were in the pirated copy of Things Fall Apart I read while in junior secondary school in Abuja, now NigeriaŌĆÖs capital. I remember no particular feeling of admiration for the images but realise now that these were likely the first works of art by a Nigerian artist I had been able to access and consciously paid attention to, even in a bastardised and over-xeroxed reproduction. Now I wonder what it would be like if an entire generation of children could be educated in art through encounters with illustrations in novels.

Susanne Wenger

Die magische Frau 1960

┬® Susanne Wenger Foundation. Photo: Martin Bilinovac

Susanne Wenger (1915ŌĆō2009), founder of the New Sacred Art Movement, was born in Graz, Austria and died in Osogbo, Nigeria. By the time of her death, her commitment to the service of Yoruba deities was unlikely to have been tempered by the fact of her birthplace. Known by the local circle of artists as Adunni Olorisa ŌĆō one who is initiated by a divine being ŌĆō her life was marked by service to a cosmology that would have seemed inconceivable during her Austrian childhood.

IŌĆÖm struck by the way the migrant narrative of her life is more prismatic than those to which we are usually accustomed: where belonging to a place is measured less by origin than by the depth of oneŌĆÖs commitment to what was once a foreign worldview.

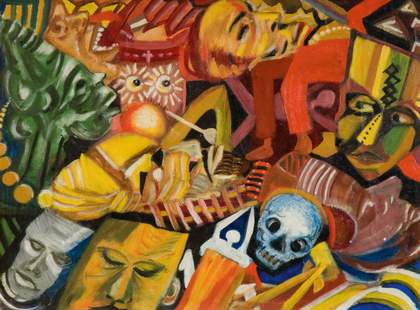

Twins Seven-Seven

DevilŌĆÖs Dog 1966

┬® Estate of Twins Seven-Seven. Photo courtesy of Iwalewahaus, University of Bayreuth

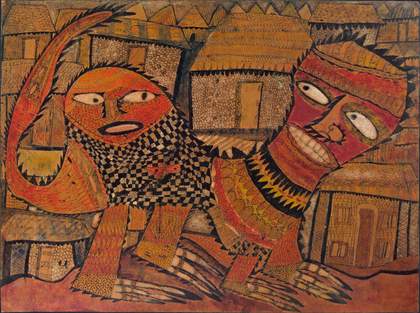

Wenger's New Sacred Art Movement was an offshoot of the Osogbo School, many of whose members ŌĆō such as Jacob Afolabi (born 1940), Rufus Ogundele (1946ŌĆō1996), Adebisi Fabunmi (born 1945), Muraina Oyelami (born 1940), Twins Seven-Seven (1944ŌĆō2011) and Asiru Olatunde (1918ŌĆō1993) ŌĆō were first introduced to artmaking in experimental workshops held in the early 1960s. In most cases, these individuals hadnŌĆÖt previously conceived of themselves as artists. Their new occupation encouraged them to intuit images from the wellspring of their Yoruba identity. Or, at least, this is what I imagine.

What thrills me about their images ŌĆō as in the work of Nike Davies-Okundaye (born 1951), who works with embroidery and fabric ŌĆō is their pluriverse of forms. They are oblique, aslant, dangly, multi-bodied, multi-perspectival. When Yoruba art was transported to the two-dimensional plane, it retained some of its sculptural character. Or perhaps it is better to say that it never lost its connection to a multi-dimensional plane, in which the living, dead and unborn coexist in symphony.

Chike C. Aniakor

Reminiscences Revisited 1996

┬® Chike C. Aniakor. National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution. Photo: Brad Simpson

In paintings by artists of the Nsukka group, associated with the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, the lines proceed with spontaneity, elegantly balancing negative and positive spaces. They are imbued with the moral compunction of Uli, an ancient mark-making tradition in Igboland, with designs applied to bodies, walls and shrines. By the time of the Nsukka membersŌĆÖ emergence as artists ŌĆō many of them came of age after the 1967ŌĆō70 Nigerian Civil War, their universityŌĆÖs walls riddled with bullets ŌĆō the hurrah of independence had faded to a sober hum of despondency. In the paintings of Obiora Udechukwu (born 1946), Olu Oguibe (born 1964) and Chike C. Aniakor (born 1939), and in sculptures by Ndidi Dike (born 1960), one senses that, after the cataclysm of war, reality had become disjointed, too warped to be represented in single or unbroken lines.

Uzo Egonu

Will Knowledge Safeguard Freedom 2 1985

┬® Estate of Uzo Egonu. Tiana & Vikram S. Chellaram. Photo ┬® SothebyŌĆÖs

Uzo Egonu (1931ŌĆō1996) was born in colonial Nigeria but left for England in 1945, long before Nigerian independence. In autumn 1989, the artist and critic Olu Oguibe had the enviable opportunity of meeting with him in preparation for writing an academic monograph on the artistŌĆÖs work. Oguibe came to London with the ŌĆśspecific aim to study and document EgonuŌĆÖs workŌĆÖ, and the book that followed, Uzo Egonu: An African Artist in the West (1995), is still the most comprehensive document on the artist to date. I am interested in the pairŌĆÖs affinity ŌĆō a loose word for the kinship they built up over two years of conversation, ŌĆśweekly at firstŌĆÖ, Oguibe wrote in the bookŌĆÖs prologue, ŌĆśthen every other weekŌĆÖ as the two spent ŌĆśnumerous mornings and afternoons looking together at his career and work.ŌĆÖ

While my academic curiosity has been satisfied by reading OguibeŌĆÖs book, I find I still wish to know something more. After all, as the novelist Anne Michaels puts it, the life of an artist ŌĆśis mostly submerged beyond our knowingŌĆÖ, lying in that twilight zone between biography and artwork.

Nigerian Modernism, ╔½┐ž┤½├Į, 8 October 2025 ŌĆō 10 May 2026.

Emmanuel Iduma is a Nigerian writer and art critic.

Nigerian Modernism is in partnership with Access Holdings and Coronation Group. Supported by Ford Foundation, The A. G. Leventis Foundation, and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. With additional support from the Nigerian Modernism Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Americas Foundation.