Lee Miller

Revenge on Culture 1940

┬® Lee Miller Archives, England 2025. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk

In 1941, the London-based American journalist and curator Ernestine Carter published Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire, a photo book that aimed to show the realities of the Blitz. It contained the work of multiple photographers, but only one was credited, CarterŌĆÖs friend and fellow American expat Lee Miller. MillerŌĆÖs picture of a nude sculpture lying among the rubble, a twisted iron bar cutting across her throat, caught the publicŌĆÖs attention and was subsequently reprinted in various magazines and newspapers, both nationally and internationally. Titled Revenge on Culture 1940, this photograph represented all that the Allies were fighting for. But its composition also harks back to the sensibility of the surrealists Miller had worked alongside in Paris a decade earlier; a real scene imbued with aspects of the bizarre.

Although she never formally identified with any official group, nor signed any manifestos, Miller was an artist whose attitude to life, love and art was steeped in the surrealist milieu and its ideals: the freedom of both imagination and desire. Her early association with the famous surrealist Man Ray is relatively well documented, as is her later war reportage, but rarely has the full scope of her significance as an artist been recognised. Tate BritainŌĆÖs new retrospective is set to change this. The exhibition also acknowledges the importance of MillerŌĆÖs adopted homeland. Born in Poughkeepsie, New York in 1907, throughout the 1920s and 1930s she spent significant time in Paris, New York and Cairo. Then, from 1939, until her death in 1977, Miller resided in England. She lived there with her lover, then husband, Roland Penrose, the British surrealist artist and collector, first in London and, from 1949, also at Farleys in East Sussex.

George Hoyningen-Huene, Lee Miller wearing sailcloth overalls by Yrande, Paris, 1930; Previous spread: Lee Miller, Revenge on Culture, London, 1940

┬® George Hoyningen-Huene Estate Archives. Photo: Victoria and Albert Museum

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Miller was 32 years old and living in London. She had been there for two years, since leaving Cairo and her Egyptian husband, the wealthy businessman Aziz Eloui Bey, after falling in love with Penrose. Her allegiance was firmly with the Allies. ŌĆśIŌĆÖd fight on a barricade so that they could continue painting so-called ŌĆ£degenerate artŌĆØ,ŌĆÖ she wrote in a letter to her brother back in America in 1940, referring to the many artist friends she had still living in France, then under Nazi occupation. Rather than returning to the safety of the United States ŌĆō as her passport allowed and her embassy had encouraged ŌĆō Miller made a conscious decision to make a home in London with Penrose, keeping calm and carrying on like everyone else in the city. Or, as she jauntily put it, writing to Audrey Withers, ŌĆśIŌĆÖd eaten the butter so IŌĆÖd better face the guns.ŌĆÖ

Withers was MillerŌĆÖs editor at British Vogue, and an important champion of her work, regularly publishing MillerŌĆÖs images throughout the war and after. But MillerŌĆÖs relationship with the magazine stretched back to the 1920s, to her first career as a model in New York. Legend has it that it was Conde╠ü Montrose Nast himself who ŌĆśdiscoveredŌĆÖ the 19-year-old Miller on a Manhattan sidewalk, instantly captivated by her androgynous beauty and ultra-modern ▓Ą▓╣░∙│”╠¦┤Ū▓į▓į▒-style bobbed hair. Soon after, a drawing of her by the celebrated French fashion illustrator Georges Lepape graced the covers of the March 1927 editions of both American and British Vogue. Miller became a regular presence in the magazineŌĆÖs pages, initially in front of the camera, but from 1930, increasingly behind the lens.

Lee Miller

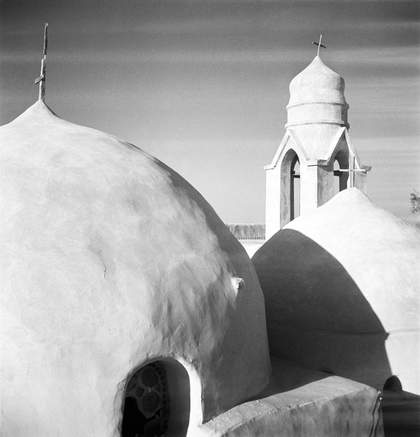

Untitled (Domes of the Monastery of Saint Mary El Sourian), Wadi Natrun, 1939

┬® Lee Miller Archives, England 2025. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk

Although Miller was introduced to photography as a child by her father Theodore, himself an enthusiastic amateur, it was only on tiring of modelling that she decided to channel her artistic energies in this particular direction. In June 1929, she returned to Paris ŌĆō where she had spent eight glorious months as an 18-year-old, falling instantly in love with the city, its people, and its artistic scene ŌĆō armed with nothing but an introductory letter from Edward Steichen, then American VogueŌĆÖs most prestigious photographer, with whom sheŌĆÖd worked in New York. She arrived and presented herself to Man Ray as his new apprentice. He was initially resistant, but Miller refused to take no for an answer. She was a quick study, and clearly possessed of her own marked talent, and their entanglement soon outgrew that of mentor and mentee. The work they produced together was deeply collaborative, even if Miller wasnŌĆÖt always given the credit she deserved. Most famously, they rediscovered the ŌĆśsolarisationŌĆÖ technique, also known as the Sabatier effect, in which negatives are briefly re-exposed to light to partially reverse the black and white tones.

Having left New York as a fe╠éted beauty on the glitzy Park Avenue party scene, Miller returned in 1932 as a celebrated photographer. Her work was much in demand, both commercially and artistically, and she relocated the studio sheŌĆÖd opened in Montparnasse in 1930 to ManhattanŌĆÖs midtown. But her time back in America was short-lived. In September 1934, she married Eloui Bey, and the newlyweds departed for a life together in the groomŌĆÖs homeland. Egypt offered Miller new creative vistas and inspiration, and her photographs from this time document her explorations, from the backstreets of Cairo through the countryŌĆÖs most remote deserts.

Lee Miller

Untitled (Reflection of Lee Miller), Guerlain Parfumerie, Paris, c.1930

┬® Lee Miller Archives, England 2025. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk

The ringed iron chimneys of the Helwan cement factory, shot vertiginously from below. A string of bright, bleached snail shells clustered along a dry tree branch. The white domes of the monastery of Saint Mary El Sourian, their curves reminiscent of the breasts and buttocks of the nudes Miller both shot and posed for while working with Man Ray. In Paris, Miller had found inspiration all around her ŌĆō elegant glass bottles in the window of the Guerlain Parfumerie with Miller herself caught in the glassŌĆÖs reflection, Vivian Maier-style; bird cages in front of ornate ironwork, metal crosshatched and layered; the carved figures on the fac╠¦ade of Notre Dame. In Egypt, it was no different, where Miller also shot her images in distinctive close-up, her compositions attuned to both the beauty, but also the surreal potential of everyday objects and scenes. An unexpected angle, frame or crop renders something once familiar, foreign. What should be inanimate is roused to sentiency. A seemingly innocuous object is imbued with symbolic power.

The summer of 1937 proved to be an important turning point in MillerŌĆÖs life. It was during a trip to Paris that June that she first met Penrose, and their romance blossomed against a backdrop of rich creative collaboration among the European artistic avant-garde. This presented a stark contrast to the boredom that she increasingly experienced in Cairo. Although sheŌĆÖd felt burnt out before arriving in Egypt, and was glad of a break from the demands of running a busy studio, as time passed, she grew restless for artistic stimulation once again. Penrose borrowed his brotherŌĆÖs house in Cornwall for a ŌĆśsudden surrealist invasionŌĆÖ, and he and Miller were joined by Man Ray and the photographerŌĆÖs then-partner Ady Fidelin, as well as the poet Paul E╠üluard and his performer and artist wife Nusch. Also in attendance were E.L.T. Mesens, the Belgium-born writer, artist and leader of the Surrealist Group in England; the Argentine-British painter and photographer Eileen Agar; and the German painter and sculptor Max Ernst and his British lover, the writer and artist Leonora Carrington. They spent July living, loving and working together, in an atmosphere of lush creative and sexual energy that continued in France that August when some of the group met up with Pablo Picasso near Cannes. There, Picasso and MillerŌĆÖs lifelong friendship began ŌĆō he painted her that summer, and she, in turn, began to photograph him. By the end of her life, he was the subject sheŌĆÖd photographed the most.

Lee Miller

Eileen Agar, Royal Pavilion, Brighton, 1937

┬® Lee Miller Archives, England 2025. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk

Miller returned to Egypt in October feeling ŌĆśchanged and glowing and renewedŌĆÖ, both as a woman newly in love and an artist freshly enthused. She filled her and Eloui BeyŌĆÖs Cairo home with works by Man Ray, Picasso and Penrose, among others. She hosted surrealist soire╠ües, joking with people that sheŌĆÖd become something of a lecturer on modern art, so often was she educating her guests. She even began making plans to start a magazine with the left-wing Egyptian surrealist group Art et Liberte╠ü.

At the same time, her profile as an artist was growing back in London. Penrose and MesensŌĆÖs exhibition Surrealist Objects & Poems at the London Gallery in November 1937 included MillerŌĆÖs Le Baiser (The Kiss): a wax arm, the sort one would have found in a manicuristŌĆÖs salon, wearing a bracelet of false teeth. The idea was conceived by Miller in Cairo, and created by Penrose under her strict written instructions. Mesens and Penrose also included several of MillerŌĆÖs photographs in their monthly London Bulletin, including her 1937 portrait of Eileen Agar ŌĆō with AgarŌĆÖs shadow profile rippling across one of the white stone columns of BrightonŌĆÖs Royal Pavilion ŌĆō and MillerŌĆÖs now famous image of the Egyptian desert, Portrait of Space 1937, which went on to directly inspire Rene╠ü MagritteŌĆÖs painting Le baiser (The Kiss) 1938.

Lee Miller

Portrait of Space, Al Bulwayeb, near Siwa, 1937

┬® Lee Miller Archives, England 2025. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk

Miller arrived in England in June 1939 to embark on a new life with her lover, but we should also understand this moment as that of an artist returning to the European avant-garde scene, which had always been her true artistic home. However, this was not the Europe she knew. It was a continent about to be plunged into war, affecting the lives of all therein. Over the next few years, her work at British Vogue became progressively expansive. Fashion shoots sat alongside photojournalism pieces about female factory workers, nurses and RAF Bomber Command. And Miller was increasingly finding her way with words, too. Note the sardonic title of You will not lunch in Charlotte Street today 1940 ŌĆō the photograph of a wide, empty street, in the middle of which sits a pint-sized, potted tree hung with a sign that reads: ŌĆśDANGER unexploded bombŌĆÖ.

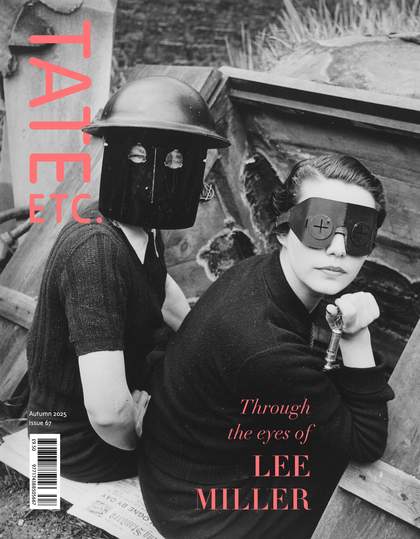

London was a city made unfamiliar by war. Buildings ripped apart by bombs turned once-recognisable streets into unknown terrain, and the boundaries between private domestic interiors and public spaces were constantly breached, the tattered remains of destroyed rooms in evidence on every corner. Miller didnŌĆÖt simply document the devastated city; she used its newly alien topography as her canvas. In a 1941 fashion shoot for Vogue, the elegance of the model is contrasted with the surrounding annihilation. Wearing a stylish Digby Morton suit and a feathered hat, the model is posed by Miller amid the wreckage of bombed buildings. Yes, this picture echoed the ethos of the magazine, which was to boost its readersŌĆÖ morale during these testing times, but there was something particular about MillerŌĆÖs surrealist-trained eye that enabled her to exploit the dramatic potential of this now uncanny cityscape with acutely evocative effect. In another picture, for instance, two women in futuristic-looking protective faceguards are transformed by MillerŌĆÖs lens into characters from a science-fiction film (see cover).

Lee Miller

Model (Elizabeth Cowell) wearing Digby Morton suit, London, 1941

┬® Lee Miller Archives, England 2025. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk

ŌĆśA piece of parachute silk fluttered from a branch near the explosive circle of a new crater. Paths of grass were corroded as if by acid, a piece of broken railing stuck out of the earth,ŌĆÖ wrote the novelist Bryher in her wartime novel Beowulf. Written at the height of the Blitz (though only published in 1956) the strange, spare precision of her prose echoed the disjointed and startling scenes in MillerŌĆÖs photographs of the city. In Non-conformist chapel 1940, for instance, bricks and rubble spill out of a doorway, as if the building is vomiting up its innards. Likewise, I think of MillerŌĆÖs photos of blitzed London when I read the great Anglo-Irish writer Elizabeth BowenŌĆÖs description of life in the British capital during these years as ŌĆśdisjected snapshotsŌĆÖ. Eerily reminiscent of the earlier Portrait of Space, taken in the Egyptian desert, Dolphin Square, Bridge of Sighs and Burlington Arcade (all 1940) are each studies of new voids that have appeared in the English capital, expanses of sky framed between ruins. In the latter, the shafts of sunlight that slice through the blasted roof imbue the image with a sense of the ethereal. It looks like a still from one of the dreamscapes in A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Michael Powell and Emeric PressburgerŌĆÖs magisterial, wartime fantasy romance film.

Capturing any such flashes of beauty became increasingly difficult once Miller made it across the Channel and advanced into the all-too-real hellscapes of mainland Europe. She had gained her credentials as a US War Correspondent for Condé Nast Publications in December 1942 but had to wait until July 1944 when accredited American female war correspondents were finally given permission to enter war zones (although they were never allowed on the front line). This granted, she immediately flew to Normandy to document the evacuation hospitals, before travelling boldly on through France. She was caught in active conflict in Saint-Malo, Brittany; watched French women accused of collaboration having their heads publicly shaved in Rennes; and arrived in the French capital only days after it was liberated, where she met up with old friends, including Picasso, Jean Cocteau, and Paul and Nusch Éluard.

Lee Miller

Fall of the citadel: Aerial bombardment, Saint-Malo, 1944

┬® Lee Miller Archives, England 2025. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk

She documented all of this in her own inimitable style, as British VogueŌĆÖs managing director Harry Yoxall later applauded: ŌĆśWho else has written equally well about G.I.ŌĆÖs and Picasso? Who else was in at the death at St. Malo and reached Paris and wrote and photographed the rebirth of the fashion salons?ŌĆÖ By this point, Miller wasnŌĆÖt only taking photographs, she was writing the copy that accompanied them too. She was VogueŌĆÖs eyes and voice in Europe, a roving reporter armed with her camera and typewriter, able to cover the most catholic of subjects.

It was gruelling, soul-destroying work, though. ŌĆśIf I could find faith in the performance of liberation I might be able to whip something into shape,ŌĆÖ she wrote to Withers from Luxembourg in October, where she was reporting on ŌĆśthe tide of refugeesŌĆÖ fleeing the German borders. ŌĆśI, myself, prefer describing the physical damage of destroyed towns and injured people to facing the shattered morale and blasted faith of those who thought ŌĆ£Things are going to be like they wereŌĆØ and of our armies [sic] disillusionment ŌĆ£Is Europe worth saving?ŌĆØŌĆÖ

The worst was still to come. In 1945, Miller followed the liberation forces through Germany as the country surrendered. ŌĆśIŌĆÖm becoming hard and hateful,ŌĆÖ she wrote to Penrose that spring, describing the pain of her encounters with ordinary German citizens. ŌĆśI glare at their blossoms and plowed [sic] fields and undestroyed villages and work myself up into such a state that I have no human kindness in me when I talk to their victims.ŌĆÖ In ŌĆśGermans Are Like ThisŌĆÖ, published in American Vogue that June, she juxtaposes two pairs of photographs with strikingly horrifying effect: ŌĆśGerman children, well-fed, healthy ... burned bones of starved prisoners,ŌĆÖ reads the caption under the first set. ŌĆśOrderly villages, patterned, quiet ... orderly furnaces to burn bodies,ŌĆÖ the second.

Lee Miller

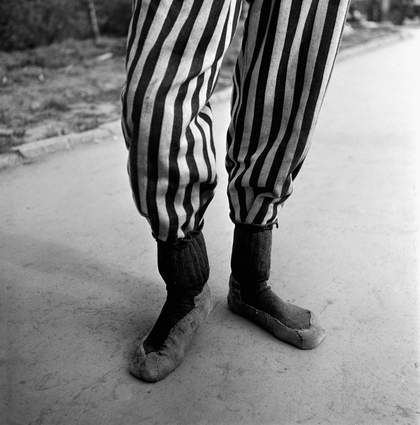

Untitled (PrisonerŌĆÖs legs), Buchenwald, 1945

┬® Lee Miller Archives, England 2025. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk

MillerŌĆÖs photographs that attest to the worst Nazi atrocities are some of the most striking and nuanced of her career. Important documentary evidence of crimes otherwise impossible to imagine, these images also engage with ideas of violence, justice, retribution and revenge. Her image of the chilling motto ŌĆśJedem das SeineŌĆÖ (To each what they deserve) engraved on the gates of Buchenwald concentration camp ŌĆō which she entered just days after it was liberated ŌĆō already points to the reckoning that would follow. She views it in reverse, with US soldiers amassed beyond the gates.

Further inside the camp, she shows the perpetrators, not as plumped-up officers of a once terrible and powerful regime but as ordinary men-turned-monsters. In Beaten SS guard 1945, she shoots her subject in grim, uncompromising close-up. His face is bloody, his civilian clothes besmeared with dirt, his eyes wide and horrifyingly vacant. But itŌĆÖs her photographs of the inmates ŌĆō both those who survived, and the bodies of those who didnŌĆÖt ŌĆō that are the most harrowing. IŌĆÖm drawn to her pictures of a group of prisoners who stand in mourning by a pile of burnt human remains, two of whom look into MillerŌĆÖs lens with piercing, unforgiving stares. As hard as it must have been to meet their eyes, Miller refused to look away, even though what she saw haunted her for the rest of her life.

MillerŌĆÖs photographs of the conflict exist in a realm of their own, somewhere between art and photojournalism, thus ŌĆśtroubling the business ŌĆō and the politics ŌĆō of war representation itself,ŌĆÖ as the exhibitionŌĆÖs curator Hilary Floe perceptively observes. Miller saw so very much, both beautiful and ugly, but more importantly, she saw things differently to the rest of us. Her work demands that we look harder ŌĆō and for longer than we might be used to, or comfortable with ŌĆō so that we, too, can see things differently.

Lee Miller, Tate Britain, 2 October 2025 ŌĆō 15 February 2026.

Lucy Scholes is a writer who lives in Oxford. She is Senior Editor at McNally Editions.

Lee Miller is supported by the Lee Miller Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons, Tate Photography Acquisitions Committee, Tate Americas Foundation and Tate Members. The media partner is The Independent. On behalf of Tate, the curatorial team of Lee Miller offer additional thanks to the Lee Miller Archives.