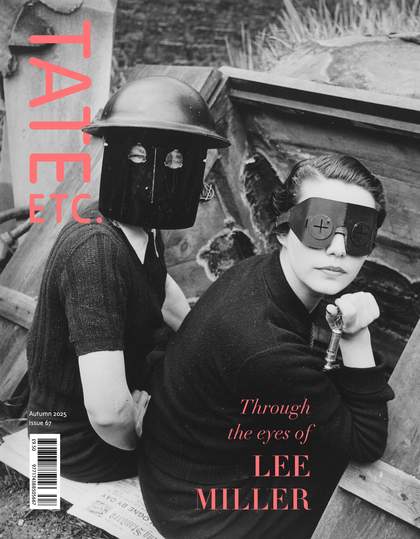

Lee Miller

Nurse Gertrude van Kirk (of New Jersey) helps a litter case to England, Normandy, 1944

© Lee Miller Archives, England 2025. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk

It is quite beautiful, the way the stretcher with the wounded soldier is being held aloft to transport him into the safety of the aircraft’s interior. The plane looks like an old Dakota, used for parachute droppings, as well as evacuating wounded soldiers during the Second World War. You can see the compassion in the hands reaching out to help this wounded man. The picture tells a story about somebody being repatriated, alive, back to their own country.

Lee Miller could not have chosen a better place to stand when she took that picture. The whole composition is perfect, especially when you consider that she took it with a Rolleiflex, a camera that is totally unsuitable for war. When I was just starting out as a photographer, I went to Berlin during the building of the wall between East and West Germany. I had only one camera, a poor relative of the Rolleiflex that Miller used. The format is very square, which limits how you can compose your photograph. It’s not suitable for taking pictures of running battles or combat. Modern war photographers use 35mm cameras, which give a wider view, more like the human eye. With that camera, she had to cover war in a different way.

Looking over the pictures that she took during the Second World War, I can tell right away that once Miller got that ticket to ride, she went off and did her own thing. She wasn’t going to be told what she could and couldn’t do. As I know from my own experiences, when covering a war, there are always problems you must push aside to get what you want. When she was in active combat zones in France, Miller would have had a lot of restrictions placed on her by the Ministry of Defence. Her achievements could only have been made possible by her strength. She must have been a very powerful woman.

You have to bear in mind that she was on assignment for Vogue, a fashion magazine that stood for things like good taste and glamour. Bringing war into that magazine – how could she have justified the situation that she was involved in? When I first became a photographer, I didn’t realise that so much responsibility comes your way if you choose a certain subject. I had to start thinking about values: Why am I here? Why am I watching people suffering whom I can’t help? Shouldn’t I have trained as a doctor? There is morality to consider when covering conflict. Miller would have come up against this too.

It’s partly because of this that I don’t think my own photography is art, and I don’t like being called an artist. When you’re photographing war and using other people’s lives to illustrate a situation, being called an artist goes against the grain. You cannot associate that with the art world; it’s shameful.

I’ve seen lots of women photographing wars since I started out. I knew one French photographer who learned how to parachute by training with the US Army in Vietnam. She was always on the frontline; there was no stopping her. But Miller didn’t come from a background of working as a reporter on a newspaper, she had been part of a circle of the most interesting intellectual people in France. She was sophisticated and glamorous. Entering the theatre of war, surrounded by so many men, it must have been an interesting time.

When Miller covered the war, and later the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau, she must have had flashbacks to her cosy days in Parisian parks, having picnics with artists and writers. She must have been a complex woman – a juggler, you see. She juggled all these different things and didn’t want to drop any one of them. She overcame an enormous volcano of problems to show that she had talent in her own right, and wasn’t going to be stopped from both using it and showing it.

Don McCullin is a photographer best known for his images of war and conflict. Coinciding with his 90th birthday, an exhibition of his work runs 9 September – 8 November at Hauser & Wirth, New York. He talked to Figgy Guyver.